Brief Overview

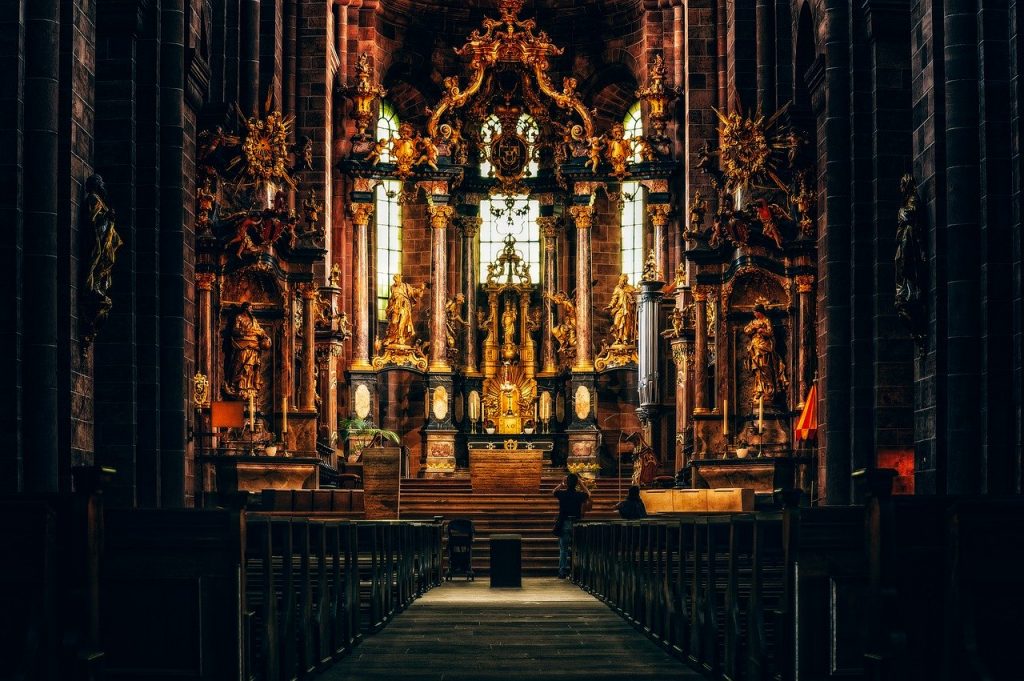

- This article examines the common claim that Christianity is merely a personal relationship with Jesus Christ rather than a structured religion.

- It explores clear biblical evidence showing that Christianity involves organized practices, rituals, and beliefs, aligning with the definition of a religion.

- Key passages from the New Testament, such as James 1:26-27 and 1 Timothy 5:4, explicitly use terms related to “religion” to describe the Christian faith.

- Jesus’ own commands, including baptism and the Lord’s Supper, establish specific actions that form a system of worship, a hallmark of religion.

- The early Church, as seen in Acts and the writings of the apostles, operated with traditions, hierarchy, and communal practices, not just individual faith.

- Catholic teaching supports this view, emphasizing that faith is expressed through both personal belief and structured religious life, as outlined in the Catechism of the Catholic Church (CCC).

Detailed Response

The Bible Uses the Word “Religion” to Describe Christianity

The New Testament does not shy away from describing the Christian faith as a religion. In James 1:26-27, the author speaks of “religion” that is acceptable to God, using the Greek word “thrēskeia,” which refers to worship or religious practice. This passage highlights that true religion involves concrete actions, such as caring for orphans and widows, rather than just internal belief. James warns that a failure to control one’s speech can render one’s religion “worthless,” implying that religion is a measurable standard of faith lived out. This is not a vague relationship but a structured way of life with expectations. The Catholic Church echoes this in its teaching that faith must be active, not passive (see CCC 1814-1816). The text does not suggest that religion is optional for Christians; rather, it is the framework through which faith is expressed. By defining “pure and faultless” religion, James shows that Christianity fits the definition of an organized system of beliefs and practices. This directly challenges the idea that Christianity is only a personal connection with God. The Bible itself, then, provides a foundation for understanding Christianity as a religion.

Paul Affirms Religion in Practice

In 1 Timothy 5:4, Paul instructs that family members should “put their religion into practice” by caring for widows, using the Greek term “eusebein,” often translated as “piety” or “godliness.” This term carries a sense of religious duty, not just personal sentiment. Paul’s words indicate that religion is something Christians are expected to enact through specific behaviors. He ties this practice to pleasing God, showing that it is an essential part of faith. The Catholic perspective aligns here, viewing such acts as expressions of charity, a virtue central to Christian life (CCC 1822-1829). This is not about an abstract relationship but about fulfilling obligations within a religious framework. Paul does not separate faith from these actions; instead, he sees them as inseparable. The implication is clear: Christianity involves a structured approach to living out belief. This passage reinforces that the New Testament authors saw their faith as a religion with practical demands. Thus, the Bible consistently presents Christianity as more than a private bond with Christ.

Jesus Established a System of Worship

Jesus’ teachings and commands provide clear evidence that He intended to establish a religion. In Matthew 22:37-40, He gives the two greatest commandments—loving God and loving neighbor—as the foundation of the law. These are not mere suggestions but directives that shape a way of life. He further institutes specific rituals, such as baptism in Matthew 28:19-20, commanding the apostles to baptize and teach obedience to His instructions. This establishes a formal process for entering and living the Christian faith. Similarly, in Luke 22:19-20, Jesus institutes the Lord’s Supper, saying, “Do this in remembrance of me,” creating a communal act of worship. The Catholic Church recognizes these as sacraments, essential to the religious life of believers (CCC 1113-1130). These commands show that Jesus envisioned a structured faith, not just a personal connection. His authority underpins these practices, making them binding on His followers. Christianity, from its inception, thus bears the marks of a religion.

The Lord’s Supper as a Religious Ritual

The institution of the Lord’s Supper in Luke 22:19-20 is a cornerstone of Christian practice. Jesus does not present it as an optional act but as a command to be repeated. The apostles understood this, as seen in 1 Corinthians 11:23-26, where Paul recounts receiving and passing on this tradition. He emphasizes its significance, noting that it proclaims Christ’s death until His return. This repetition and communal nature make it a religious ritual, not a casual gathering. The Catholic Church teaches that this is the Eucharist, a central act of worship (CCC 1322-1419). Early Christians observed it regularly, indicating a structured practice from the start. Paul’s correction of abuses in Corinth shows that it was taken seriously as a sacred rite. This is not a spontaneous expression of faith but a deliberate religious act. The Bible thus supports the idea that Christianity includes formal worship.

Baptism as a Foundational Rite

Baptism, commanded in Matthew 28:19-20, further demonstrates that Christianity is a religion. Jesus ties it to making disciples, placing it at the heart of entering the faith. The act involves a specific formula—baptizing in the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit—showing its ritualistic nature. The early Church followed this, as seen in Acts 2:38-41, where thousands were baptized on Pentecost. This was not a private decision but a public, communal event. The Catholic Church views baptism as a sacrament that initiates one into the Church (CCC 1213-1284). It carries obligations, such as obedience to Christ’s teachings, as Jesus Himself states. This structure contradicts the notion of Christianity as only a relationship. Baptism marks the beginning of a religious life, not just a personal bond. The Bible presents it as an essential practice, reinforcing Christianity’s religious character.

Apostolic Tradition Supports Religion

The apostles did not view Christianity as a loose collection of beliefs but as a faith with traditions. In 1 Corinthians 11:2, Paul praises the Corinthians for holding to the traditions he delivered. These include the Lord’s Supper, showing that rituals were part of the faith from the beginning. In 2 Thessalonians 2:15, he urges believers to hold to traditions taught by word or letter, indicating both oral and written authority. This dual transmission is a key Catholic principle, known as Sacred Tradition (CCC 75-83). The traditions were not optional but authoritative, shaping Christian practice. The early Church’s adherence to them shows a structured religion, not just a personal faith. Paul’s words suggest that these traditions are divine in origin, not human inventions. This challenges the idea that Christianity lacks religious form. The Bible affirms that tradition is integral to the faith.

Early Christian Worship Was Structured

The practices of the early Christians, as recorded in Acts 2:42, reveal a religious framework. They devoted themselves to the apostles’ teaching, fellowship, breaking of bread, and prayer—all communal acts. This was not a haphazard gathering but a consistent pattern of worship. The Catholic Church sees this as the foundation of its liturgical life (CCC 1345-1355). The regularity of these practices indicates a system, not just spontaneous faith. The breaking of bread likely refers to the Lord’s Supper, tying it to Jesus’ command. Prayer and teaching further suggest a structured approach to faith. This community life was essential, not optional, for early believers. The Bible presents this as the norm, not an exception. Christianity, from its earliest days, thus operated as a religion.

The Church Had a Clear Hierarchy

The early Church was not a free-for-all but had a defined structure. In Acts 15, the Council of Jerusalem shows leaders like Peter and James making authoritative decisions. This council addressed disputes, issuing decrees for all believers to follow. Paul’s letters, such as 1 Timothy 3:1-13, outline qualifications for bishops and deacons, indicating roles within the Church. These positions carried responsibility, not just influence. The Catholic Church builds on this, teaching that such hierarchy is apostolic in origin (CCC 857-896). In Acts 9:17-19, Paul’s baptism and time with the apostles show his submission to this structure. Even his later ministry required approval from Church leaders (Galatians 2:1-10). This organization is a hallmark of religion, not a mere relationship. The Bible supports a structured Church from the outset.

Tradition Is Biblical and Necessary

Some argue that traditions are unbiblical, citing Mark 7:8 or Matthew 15:6, where Jesus critiques human traditions. However, these passages condemn traditions that contradict God’s word, not all traditions. In 2 Thessalonians 2:15, Paul explicitly endorses traditions as part of the faith. These include practices like the Lord’s Supper and baptism, handed down from Christ. The Catholic Church distinguishes between Sacred Tradition and human customs (CCC 83). The former is divine and binding; the latter is cultural and adaptable. Paul’s praise in 1 Corinthians 11:2 shows that tradition was valued when aligned with God’s will. The early Church relied on it alongside Scripture, as the New Testament was not yet complete. This balance refutes the idea that Christianity rejects religious structure. The Bible affirms tradition as a vital component of faith.

Repetitious Prayer Is Not Condemned

Critics often point to Matthew 6:7, where Jesus warns against “vain repetitions” in prayer, to argue against religious practices like Catholic prayers. However, the Greek term here, “battologeō,” refers to meaningless babbling, not repetition itself. Scripture elsewhere supports repeated prayer, such as Revelation 4:8, where heavenly beings ceaselessly say, “Holy, holy, holy.” Jesus Himself repeats His prayer in Mark 14:32-39, showing that repetition is not inherently wrong. The Catholic Church teaches that prayers like the Our Father are meaningful when offered with devotion (CCC 2559-2565). Psalm 136 repeats a refrain 26 times, yet it is inspired Scripture. The issue is the heart, not the act of repetition. This misreading of Matthew 6:7 does not undermine Christianity as a religion. Instead, it highlights the need for sincere practice. The Bible does not reject structured prayer.

The Early Church Fathers Confirm Religion

Writings from early Church leaders, like Justin Martyr in his First Apology (circa 150 AD), describe Sunday worship with readings, prayers, and the Eucharist. This mirrors the structure seen in Acts and Paul’s letters. Ignatius of Antioch, writing around 107 AD, stresses obedience to bishops and the centrality of the Eucharist, calling it the “Catholic Church.” These accounts, from within a generation of the apostles, show a consistent religious practice. The Catholic Church sees this as evidence of its continuity with apostolic faith (CCC 1345). The rituals and hierarchy were not later additions but present early on. This refutes claims that Christianity was originally unstructured. The Fathers’ testimony aligns with biblical patterns of worship and authority. Their words carry weight as witnesses to the faith’s origins. Christianity, historically, is undeniably a religion.

Faith and Works Together Form Religion

The Bible ties faith to action, not just belief. In James 2:14-26, James argues that faith without works is dead, using Abraham as an example. This is not about earning salvation but showing faith through deeds. The Catholic Church teaches that faith and works cooperate in the Christian life (CCC 1814-1816). Jesus’ commands, like loving one’s neighbor (Matthew 22:39), require action, not just sentiment. Paul’s call to care for widows (1 Timothy 5:4) reflects this balance. The idea of “faith alone” apart from religious practice is not biblical. Christianity demands a lived faith, which fits the definition of religion. This integration of belief and practice is central to Catholic doctrine. The Bible thus presents a faith that is inherently religious.

The Covenant Framework Is Religious

Jesus frames His mission in terms of a covenant, saying in Luke 22:20, “This cup is the new covenant in my blood.” Covenants in Scripture, like those with Abraham or Moses, involve rules, rituals, and community. The Catholic Church sees the Church as the fulfillment of this covenant (CCC 781-810). The Lord’s Supper and baptism are covenantal acts, binding believers to Christ and each other. This is not a casual relationship but a formal bond with obligations. The Old Testament covenants included worship and laws, which Jesus builds upon. The early Church understood this, as seen in its structured practices. A covenantal faith is inherently religious, not merely personal. The Bible uses this framework consistently. Christianity, as a covenant, is a religion.

The Relationship Analogy Falls Short

While Christianity includes a personal relationship with Christ, this does not exclude its religious nature. A relationship with God, like a marriage, involves commitments and actions, not just feelings. In Ephesians 5:25-32, Paul compares the Church to Christ’s bride, a bond with structure and duties. The Catholic Church teaches that this relationship is lived through the sacraments and community (CCC 1616-1617). Jesus’ commands to obey and worship show that the relationship has form. A marriage without vows or shared life is incomplete; so too is faith without religion. The Bible does not separate the two but unites them. The “relationship, not religion” slogan oversimplifies the faith. It ignores the communal and ritual aspects Scripture emphasizes. Christianity is both, not one or the other.

Misunderstandings of Religion Persist

Some reject “religion” as man-made, contrasting it with a “pure” relationship with Christ. Yet James 1:27 defines religion positively when aligned with God’s will. The term has been misused, but the Bible redeems it for Christian use. The Catholic Church clarifies that true religion flows from divine revelation, not human invention (CCC 28-35). Jesus and the apostles established practices that fit the definition of religion. Critics often project modern biases onto the term, ignoring its biblical meaning. The early Church did not see religion as opposed to faith but as its expression. This misunderstanding distorts the biblical witness. The faith has always been religious in nature. Correcting this view restores the fullness of Christianity.

The Catholic Church Preserves This Truth

The Catholic Church has consistently taught that Christianity is a religion rooted in Christ’s commands and apostolic tradition. Its sacraments, like baptism and the Eucharist, reflect biblical mandates (CCC 1113-1130). Its hierarchy traces back to the apostles, as seen in Acts and Paul’s letters (CCC 857-896). The Church’s liturgy continues the worship of the early Christians, as Justin Martyr describes. This continuity shows that religion is not a corruption but a fulfillment of the faith. The Catechism ties belief to practice, faith to community (CCC 166-184). Critics who reject this often overlook the Bible’s own evidence. The Church’s structure is not an addition but an inheritance. It embodies the religious life Scripture prescribes. Catholicism thus upholds Christianity as a religion.

Historical Evidence Reinforces Religion

Beyond Scripture, early Christian writings confirm a religious framework. Ignatius of Antioch’s emphasis on bishops and the Eucharist shows a structured Church by 107 AD. Justin Martyr’s account of Sunday worship mirrors Acts’ description of early practice. These sources, close to the apostolic era, refute claims of a non-religious Christianity. The Catholic Church sees itself as preserving this tradition (CCC 77-79). The rapid spread of a consistent liturgy and hierarchy suggests an inherent structure. This was not a later development but a continuation of Christ’s intent. The historical record aligns with the biblical one. Christianity’s religious nature is clear across time. The evidence leaves little room for doubt.

Addressing Common Objections

Opponents argue that rituals and hierarchy distance believers from God, citing Mark 7:8. Yet Jesus critiques only traditions that nullify God’s word, not all structure. The apostles’ practices, like the Lord’s Supper, were divinely instituted, not human inventions. The Catholic Church distinguishes between sacred and cultural traditions (CCC 83). Another objection is that repetition in prayer is “vain,” per Matthew 6:7. Scripture itself, however, uses repetition without condemnation (Revelation 4:8). The issue is intent, not form. These objections misread the Bible and ignore its broader context. Christianity’s religious elements are biblical, not deviations. The objections fail under scrutiny.

A Balanced View of Faith

Christianity is not a choice between relationship and religion but a union of both. The Bible shows faith expressed through worship, community, and obedience. Jesus’ commands and the apostles’ actions establish this balance. The Catholic Church teaches that personal faith flourishes within a religious framework (CCC 161-165). The “relationship only” view neglects the communal and covenantal aspects of Scripture. A religion without relationship is empty, but a relationship without religion lacks form. The Bible integrates the two seamlessly. Early Christians lived this out, as Acts and the Fathers attest. Catholicism reflects this biblical model. The faith is complete as a religion rooted in Christ.

Conclusion: Christianity Is a Religion

The Bible leaves no doubt that Christianity is a religion, not just a relationship. From James 1:26-27 to Jesus’ commands in Matthew 28:19-20, it presents a faith with structure, rituals, and community. The apostles built on this, establishing traditions and hierarchy seen in Acts and Paul’s letters. Early Christian writings confirm this pattern continued unbroken. The Catholic Church upholds this as the faith delivered by Christ (CCC 171-175). The “relationship, not religion” claim lacks biblical support and oversimplifies the evidence. Christianity demands both personal faith and religious practice. The two are not opposed but complementary. Scripture and history affirm this truth. Christianity, at its core, is a religion established by Christ Himself.