Brief Overview

- This article examines the reported Eucharistic miracle in Kumasi, Ghana, from the 1990s, involving a Protestant photographer who allegedly captured an image of Jesus Christ.

- The incident is said to have occurred during a Corpus Christi procession, a Catholic celebration honoring the Eucharist.

- According to the story, the skeptical photographer intended to use his photographs to criticize Catholic practices but was shocked by the miraculous outcome.

- The developed film supposedly revealed an image of Jesus, leading to the photographer’s dramatic reaction and eventual confession.

- While this account has circulated among some Catholic communities, it lacks official Church recognition and verifiable evidence.

- The article will provide a scholarly Catholic perspective, analyzing the event’s theological significance and historical context.

Detailed Response

The Context of the Corpus Christi Procession

The Corpus Christi procession is a significant Catholic tradition celebrating the Real Presence of Jesus Christ in the Eucharist. Established in 1264 by Pope Urban IV following the Eucharistic miracle of Bolsena, this feast occurs on the Thursday after Trinity Sunday, or the following Sunday in some regions. In Kumasi, Ghana, during the 1990s, such processions would have been a public display of faith, often involving a monstrance—a vessel used to display the consecrated host. The story claims a Protestant photographer observed this event and perceived it as idolatry, a common critique from some non-Catholic Christians who reject the doctrine of transubstantiation. His intention, according to the narrative, was to document the procession to challenge Catholic beliefs. This context sets the stage for the alleged miracle. Ghana, with its growing Catholic population in the late 20th century, was a place where such religious tensions could arise. The photographer’s skepticism reflects broader Protestant objections to Catholic Eucharistic devotion. However, no specific date or official record ties this story to a documented procession in Kumasi. The lack of precise historical details raises questions about its authenticity.

The Photographer’s Actions and Intentions

The Protestant photographer, described as a professional, reportedly took multiple photographs of the monstrance during the procession. His goal, as the story suggests, was to provide evidence for non-Catholic Christians that Catholics worship a “wafer god”—a derogatory term implying the Eucharist is merely bread, not Christ’s body. This aligns with theological differences, as many Protestant denominations view the Eucharist symbolically rather than as a literal presence (see Catechism of the Catholic Church, CCC 1374). The act of photographing religious rituals for critique is not uncommon in interfaith debates. In this case, the photographer’s actions were deliberate, aimed at gathering visual proof. After the event, he took his film to a photo lab for development, expecting standard images of the procession. The narrative hinges on his disbelief in Catholic teachings, making the subsequent outcome more striking. No historical evidence identifies this individual or confirms his profession. The story’s reliance on an unnamed figure complicates efforts to verify it. Nevertheless, his initial intent frames the miracle as a moment of divine correction.

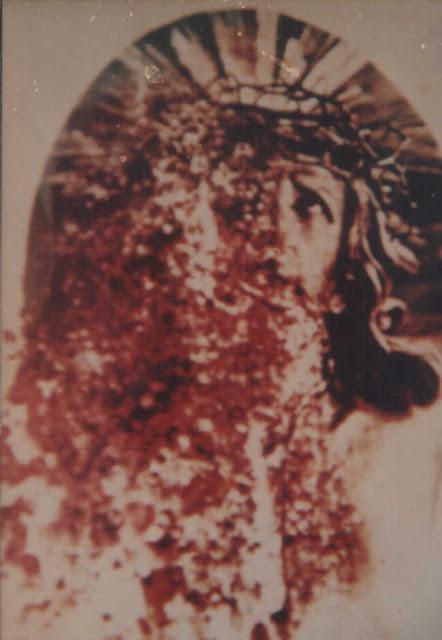

The Miraculous Image Emerges

At the photo lab, the developed film reportedly revealed an unexpected image: the face of Jesus Christ. This outcome stunned the photographer, who initially argued with lab workers, insisting the image wasn’t his. The workers allegedly showed him the negatives, proving the photo came from his film. This detail is central to the miracle claim, suggesting a supernatural intervention altered the expected result. Eucharistic miracles often involve visible signs, such as bleeding hosts or preserved flesh, but an image appearing on film is rare. The story implies the monstrance, holding the consecrated host, became a conduit for this manifestation. The photographer’s shock underscores the contrast between his skepticism and the apparent evidence. Without the negatives or original photos, however, this remains anecdotal. The lab workers’ role in recognizing the image’s significance adds a communal element to the account. Still, no physical evidence or lab documentation has surfaced to support this claim.

The Photographer’s Reaction

The narrative states that upon seeing the image and confirming its source, the photographer fainted. This dramatic reaction highlights the emotional and spiritual impact of the alleged miracle. Fainting suggests a physical response to an overwhelming realization, possibly of divine presence. After being revived, he confessed his original intent and the events leading to the discovery. This confession is a key turning point, framing the miracle as a moment of conversion or at least acknowledgment. In Catholic tradition, such reactions are not uncommon in miracle stories, where skeptics encounter undeniable signs (e.g., the miracle of Lanciano). The photographer’s shift from critic to witness aligns with this pattern. However, the lack of a named individual or firsthand testimony limits the story’s credibility. His collapse and confession are compelling but unverified. The absence of follow-up details about his life further weakens the narrative’s historical weight.

The Photo Lab’s Response

The photo studio, recognizing the image as miraculous, reportedly began developing the negatives to share it widely. This action suggests the workers saw the event as extraordinary, beyond a mere photographic anomaly. In the 1990s, photo labs in Kumasi would have used analog processes, making accidental images unlikely without manipulation. The decision to spread the image implies a belief in its spiritual value, possibly driven by Catholic staff or local religious sentiment. This step transformed a private incident into a public phenomenon, according to the story. The studio’s role amplifies the miracle’s reach, fitting the Catholic emphasis on sharing faith. Yet, no copies of this image are widely circulated or archived in Church records. The lack of physical evidence raises doubts about the studio’s actions. If true, such an image would likely have gained significant attention in Ghana’s Catholic community. The absence of documentation suggests the story may be exaggerated or apocryphal.

Theological Significance in Catholic Teaching

From a Catholic perspective, this alleged miracle reinforces the doctrine of the Real Presence. The Church teaches that the Eucharist is truly Christ’s body, blood, soul, and divinity (CCC 1374). Eucharistic miracles, like those in Bolsena or Lanciano, serve to affirm this belief, often occurring during times of doubt. The Kumasi event, if true, would fit this pattern, targeting a skeptic to reveal divine truth. The appearance of Jesus’ face on film could be seen as a modern sign, adapting traditional miracles to contemporary technology. Catholic theology distinguishes between the miracle of transubstantiation at every Mass and extraordinary events like this (CCC 1376). The latter build faith without altering the Eucharist’s essence. The photographer’s Protestant background makes the story a potential bridge for ecumenical dialogue. However, without Church approval, it remains a private revelation, not a doctrine-defining event. The theological weight hinges on verification, which is lacking here.

Historical Precedents for Eucharistic Miracles

Eucharistic miracles have a long history in Catholicism, often involving physical transformations. The miracle of Lanciano (8th century) saw bread turn to flesh, later confirmed as cardiac tissue. Bolsena (1263) featured a bleeding host, prompting the Corpus Christi feast. These events share a pattern: a doubting priest or skeptic encounters a visible sign. The Kumasi story echoes this, with the photographer as the skeptic. Unlike earlier miracles, it involves photography, a modern medium, suggesting divine adaptability. Historical miracles are typically investigated by Church authorities and preserved as relics. The Kumasi case lacks such scrutiny or tangible remains. While plausible within Catholic tradition, its uniqueness requires evidence beyond oral accounts. The precedent exists, but the execution differs significantly.

The Role of Photography in Miracles

Photography’s involvement sets this story apart from traditional miracles. In the 1990s, film photography was common, and unprompted images would be extraordinary. Catholic history includes few photographic miracles, though some claim images of Mary (e.g., Zeitoun, Egypt, 1968). The Kumasi event suggests Jesus’ image emerged spontaneously, a rare claim. Photography offers a verifiable medium, yet no prints or negatives are available. This absence undermines the story’s strength, as physical evidence would bolster its case. The medium could symbolize God’s presence in modern life, but without proof, it’s speculative. The photographer’s profession adds irony—his tool of skepticism became a vessel of faith. The lack of documentation contrasts with photography’s potential for clarity. This gap highlights the story’s reliance on testimony over substance.

The Spread of the Image

The narrative claims the photo studio spread the image, implying it reached a wider audience. In a Catholic stronghold like Kumasi, this could inspire devotion or debate. The 1990s saw Ghana’s Catholic population grow, with public faith expressions common. A miraculous image would likely circulate among parishes or in local media. However, no record exists of such an image gaining prominence. Catholic tradition encourages sharing signs of faith, as seen in pilgrimage sites. The story’s assertion fits this pattern but lacks follow-through. If widespread, the image might appear in Church archives or devotional literature. Its absence suggests limited impact or fabrication. The spread remains a hypothetical outcome without evidence.

Church Investigation and Recognition

The Catholic Church has a rigorous process for validating miracles, involving bishops and scientific study. Recognized Eucharistic miracles, like those in Buenos Aires (1996) or Sokolka (2008), underwent scrutiny and gained approval. The Kumasi story lacks any mention of official investigation. For it to be authentic, the local bishop would need to examine the photographer’s testimony, the negatives, and the image. No such process is documented in Kumasi from the 1990s. The Church distinguishes between private revelations and public doctrine (CCC 67), and this falls into the former. Without approval, it holds no authoritative weight. The absence of records suggests it never reached formal review. Local oral tradition may sustain it, but that’s insufficient for recognition. This gap is a critical flaw in the narrative.

Cultural Context in Ghana

Ghana’s religious landscape in the 1990s included a strong Catholic presence alongside Protestant and Pentecostal growth. Kumasi, a major city, hosted vibrant Catholic communities, making a Corpus Christi procession plausible. Protestant skepticism toward Catholic practices, like Eucharistic adoration, was common, fitting the photographer’s stance. A miracle in this setting could serve as a unifying or divisive event. Ghanaian Christianity often embraces the miraculous, with Pentecostals reporting healings and visions. A Catholic miracle involving Jesus’ image aligns with this openness. However, no widespread Catholic testimony from Kumasi supports this story. The cultural fit is strong, but the lack of documentation weakens its claim. Local faith could amplify the tale, yet it remains unverified. This context explains its appeal but not its historicity.

Protestant-Catholic Tensions

The photographer’s Protestant background highlights tensions between denominations. Protestant reformers, like Martin Luther, rejected transubstantiation, favoring a symbolic view (John 6:53-58 debates persist). In Ghana, such differences fueled theological disputes. The miracle, if true, challenges Protestant critiques by offering visual proof of Catholic belief. The photographer’s conversion-like response suggests a resolution to this conflict. Catholic narratives often use miracles to affirm doctrine against doubt. This story fits that mold but lacks substance to bridge the gap. Protestant reactions in Ghana remain undocumented, reducing its ecumenical impact. The tension is real, but the resolution is speculative. This dynamic adds depth yet underscores the need for evidence.

Evaluating the Evidence

The story’s evidence rests on oral tradition: the photographer’s account, the lab workers’ actions, and the image’s spread. No photographs, negatives, or firsthand witnesses are available. Catholic miracle claims typically involve relics or scientific analysis (e.g., Lanciano’s tissue tests). The Kumasi case offers none of these. The photographer’s anonymity and the lack of Church records further erode its credibility. Eyewitness consistency and physical proof are standard for validation. This narrative falls short on both. While compelling, it resembles folklore more than fact. The absence of tangible evidence distinguishes it from approved miracles. Scholarly caution is warranted given these deficiencies.

Possible Explanations

Several explanations could account for the story. A genuine miracle is one, aligning with Catholic belief in divine signs. Alternatively, a photographic error—double exposure or contamination—might produce an unexpected image, misinterpreted as Jesus. Human perception often sees familiar faces in random patterns (pareidolia). The photographer’s shock could stem from coincidence, not divinity. Fraud by the lab or storyteller is another possibility, though unproven. Catholic theology allows for miracles but doesn’t require accepting every claim (CCC 67). A natural explanation doesn’t negate faith, nor does a lack of proof disprove the event. The story’s ambiguity invites skepticism and belief alike. Without evidence, no conclusion is definitive.

Impact on Faith

If true, this miracle could strengthen Catholic faith, especially in Ghana. Seeing Jesus’ face might affirm the Eucharist’s reality for believers (John 20:29 applies). The photographer’s reaction mirrors conversion stories, inspiring others. Eucharistic miracles historically boost devotion, as with Corpus Christi’s origins. However, its unverified status limits its influence. For skeptics, it might prompt reflection, though Protestants may dismiss it. The story’s power lies in its personal impact, not institutional weight. Without recognition, its effect is localized and anecdotal. Faith doesn’t depend on such events, but they can reinforce it. This tale’s legacy is uncertain due to its obscurity.

Comparison to Approved Miracles

Approved miracles, like Buenos Aires (1996), involve bleeding hosts confirmed as heart tissue. Sokolka (2008) showed similar transformation, validated by experts. The Kumasi story lacks physical change or analysis, relying on an image. Approved cases have relics and Church endorsement; Kumasi has neither. The process—investigation, documentation, approval—is absent here. Historical miracles often convert skeptics, as in Bolsena, paralleling this tale. Yet, their preservation contrasts with Kumasi’s ephemerality. The photographer’s role mirrors doubting priests in other stories, but evidence sets them apart. Approved miracles carry doctrinal weight; this does not. The comparison highlights its weakness.

Scholarly Catholic Perspective

Catholic scholars approach such stories with caution. Miracles affirm faith but aren’t essential (CCC 548). The Church prioritizes the Eucharist’s daily miracle over extraordinary signs. Private revelations, like Kumasi, require discernment, not blind acceptance (CCC 67). The lack of evidence aligns it with unverified claims, not doctrine. Scholars value historical and scientific rigor, both absent here. The story’s appeal lies in its simplicity, not its strength. It fits Catholic patterns but lacks substantiation. Faith rests on Christ, not unproven events (Hebrews 11:1). This perspective balances openness with scrutiny.

Lessons for Believers

This story teaches that God can work through skeptics, as in Acts 9:1-19 with Paul. It suggests divine patience with doubt, offering signs to guide. Believers might see it as a call to trust the Eucharist’s reality. It also warns against dismissing others’ faith, promoting dialogue. The lack of proof reminds Catholics to focus on essentials, not sensationalism. Miracles can inspire, but faith endures without them. The photographer’s journey, if true, models humility before mystery. For Ghanaian Catholics, it could affirm local devotion. The lesson is personal, not universal, due to its uncertainty. Faith grows through reflection, not just signs.

Addressing Skeptics

Skeptics might question the story’s plausibility. Photography errors or hoaxes are logical critiques. The lack of evidence supports their doubt, as does the anonymous source. Catholics counter that miracles defy natural explanation, pointing to verified cases. The story’s intent—affirming faith—matters more than its historicity. Skeptics need not accept it, as it’s not dogma. Dialogue could explore why such tales persist across cultures. The absence of proof doesn’t disprove God, only this event. Catholics invite skeptics to consider broader evidence, like Lanciano. Mutual respect, not proof, bridges this gap.

Conclusion

The Kumasi Eucharistic miracle remains an intriguing but unverified tale. It aligns with Catholic belief in the Real Presence and miracle traditions. The photographer’s transformation echoes historical patterns, yet evidence is absent. The Church’s silence suggests it’s a local legend, not a recognized event. Its value lies in personal inspiration, not doctrinal weight. Ghana’s faithful may cherish it, but scholars demand more. Compared to approved miracles, it lacks substance. Faith doesn’t hinge on this story, but it can prompt reflection. The question of its truth persists, unanswered by history. Catholics hold to the Eucharist’s mystery, with or without such signs.

This is the Eucharistic image that was developed from the film:

For those who don’t know what a monstrance is. Below is an image of it:

A monstrance is the vessel used in the Roman Catholic Church to display the consecrated Eucharistic host, during Eucharistic adoration or Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament.

Signup for our Exclusive Newsletter

- Add CatholicShare as a Preferred Source on Google

- Join us on Patreon for premium content

- Checkout these Catholic audiobooks

- Get FREE Rosary Book

- Follow us on Flipboard

-

Discover hidden wisdom in Catholic books; invaluable guides enriching faith and satisfying curiosity. Explore now! #CommissionsEarned

- The Early Church Was the Catholic Church

- The Case for Catholicism - Answers to Classic and Contemporary Protestant Objections

- Meeting the Protestant Challenge: How to Answer 50 Biblical Objections to Catholic Beliefs

As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. Thank you.