Brief Overview

- The doctrine of the Trinity is a foundational belief in Catholicism, expressing one God in three distinct Persons: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

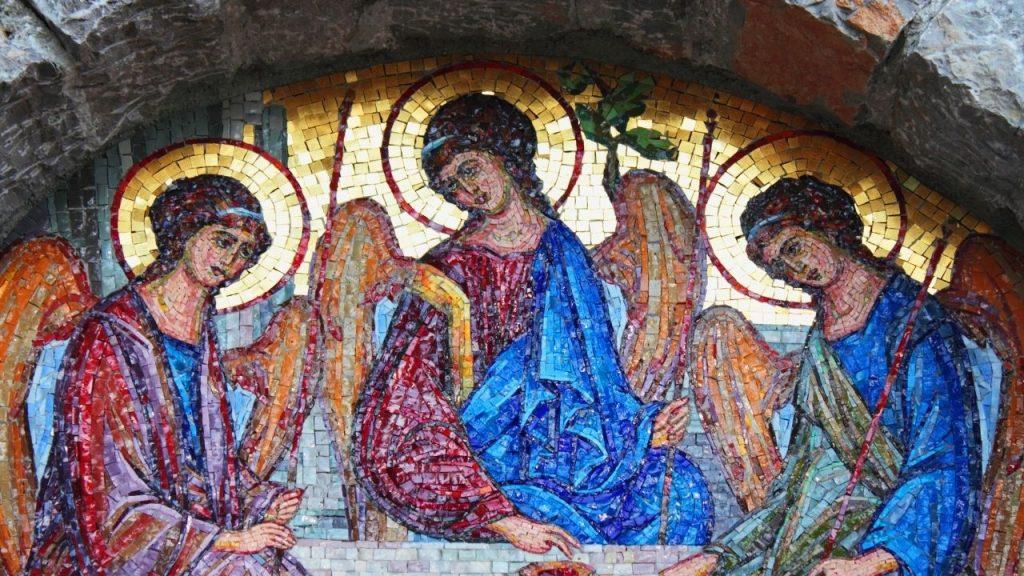

- Throughout history, Catholic artists and theologians have used symbols to represent this complex mystery in ways that are accessible to the faithful.

- Many of these symbols originated in the early centuries of Christianity, reflecting both theological truths and cultural influences.

- Some symbols, like the triangle and the shamrock, are widely recognized, while others remain less familiar to modern Catholics.

- These ancient symbols served as tools for catechesis, helping to explain the unity and distinction within the Trinity.

- This article explores lesser-known ancient symbols of the Trinity, grounded in Catholic tradition and teaching.

Detailed Response

The Importance of Symbols in Catholic Tradition

The Trinity is central to Catholic faith, defining God as one in essence yet three in Persons. This belief, affirmed in the Catechism of the Catholic Church (CCC 232-267), is not easily grasped by human reason alone. Early Christians faced the challenge of expressing this mystery without violating the Jewish prohibition on depicting God in human form. As a result, they turned to abstract symbols to convey theological truths. These symbols were not mere decorations but tools for teaching and contemplation. They bridged the gap between the infinite nature of God and the limited understanding of believers. Over time, the Church adopted and adapted symbols from various cultures. This practice allowed the faith to spread while maintaining its core teachings. Symbols of the Trinity, in particular, highlight both the unity and the distinction of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Understanding their origins and meanings deepens appreciation for Catholic theology and art.

The Shield of the Trinity: A Medieval Teaching Tool

One lesser-known symbol is the Shield of the Trinity, also called the Scutum Fidei or “Shield of Faith.” This diagram emerged around the 13th century, though its roots may trace back earlier. It consists of four circles connected by lines, with three outer circles labeled “Father,” “Son,” and “Holy Spirit,” and a central circle labeled “God.” The lines between the outer circles and the center state “is,” while lines between the outer circles state “is not.” This layout visually explains that each Person is God, yet distinct from the others. The symbol was widely used in medieval Europe, appearing in manuscripts, stained glass, and carvings. It served as a concise summary of the Athanasian Creed, which defends the doctrine of the Trinity. The Shield of the Trinity was especially valuable in an era when literacy was low. Its geometric clarity made it a powerful catechetical tool. Today, it remains a precise illustration of Trinitarian theology.

The Triquetra: A Celtic Connection

The triquetra, often called the Trinity Knot, is another ancient symbol with ties to the Trinity. It features three interlocking arcs forming a continuous shape, sometimes encircled by a ring. This design likely originated in pre-Christian Celtic culture, symbolizing concepts like land, sea, and sky. Early Christians in Ireland adapted it to represent the Trinity, emphasizing the unity of the three Persons. The continuous line suggests eternity, while the three arcs reflect distinction. The triquetra appears in the famous Book of Kells, a 9th-century manuscript of the Gospels. Its use in Christian art grew as missionaries, like St. Patrick, evangelized Celtic regions. The symbol’s simplicity made it effective for teaching converts. Though its pagan origins are debated, the Church embraced it as a fitting image of God’s triune nature. The triquetra remains a subtle yet profound emblem in Catholic tradition.

The Fleur-de-Lis: Beyond French Royalty

The fleur-de-lis, a stylized lily, is best known as a symbol of French heritage, but it also represents the Trinity. Its three petals, bound at the base, mirror the three Persons united in one Godhead. Early Christians saw the lily as a sign of purity, often linking it to the Virgin Mary. However, its Trinitarian meaning emerged in medieval Europe, particularly in France. Legend holds that Clovis, king of the Franks, adopted it after his baptism in 496 AD, associating it with divine favor. The three petals were interpreted as the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, with the band below symbolizing their shared divine nature. This symbol adorned churches, manuscripts, and royal insignia. Its dual association with Mary and the Trinity reflects the interconnectedness of Catholic doctrines. Though less prominent today as a Trinitarian symbol, it retains historical significance. The fleur-de-lis shows how cultural symbols were sanctified for theological purposes.

The Borromean Rings: Unity in Distinction

The Borromean Rings consist of three interlocking circles that cannot be separated, yet no two are directly linked without the third. This geometric figure, named after the Italian Borromean family who used it in their coat of arms, symbolizes the Trinity effectively. Each ring represents one Person of the Trinity, distinct yet inseparable from the others. If one ring is removed, the remaining two fall apart, illustrating the essential unity of the Godhead. The symbol’s origins are uncertain, but it appeared in Christian contexts by the Middle Ages. St. Augustine referenced a similar concept in the 4th century, describing three rings of one substance. The Borromean Rings emphasize that the Trinity is not three independent entities but a single, indivisible God. This symbol was less common in art than the triangle or shamrock, yet its precision appeals to theologians. It offers a mathematical analogy for a mystery beyond human comprehension. The Borromean Rings remain a striking visual of Trinitarian unity.

The Vesica Piscis: A Symbol of Divine Union

The vesica piscis, meaning “fish bladder” in Latin, is formed by two overlapping circles, creating an almond-shaped center. This shape has ancient roots, appearing in Christian art as early as the 4th century. The overlapping section symbolizes the unity of the Father and Son, while the surrounding areas suggest the Holy Spirit. Its resemblance to a fish ties it to early Christian symbolism, as seen in John 21:11. The vesica piscis also reflects Christ’s dual nature—divine and human—uniting in one Person. In Trinitarian terms, it illustrates the shared essence of the three Persons. The symbol often framed sacred images in medieval architecture and manuscripts. Its simplicity made it versatile for teaching the faithful. Though not exclusively a Trinity symbol, its use in this context highlights God’s relational nature. The vesica piscis bridges geometry and theology in Catholic tradition.

The Trefoil: A Gothic Favorite

The trefoil is a design of three overlapping circles or lobes, often seen in Gothic architecture. It resembles a three-leaf clover but is more stylized, with a focus on symmetry. In Catholic churches, it frequently appears in stained glass and stone tracery. The three lobes represent the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, united in one form. The trefoil’s association with the Trinity dates to the Middle Ages, when it adorned cathedrals across Europe. Its shape suggests both distinction and harmony, key aspects of Trinitarian doctrine. Unlike the shamrock, which is natural, the trefoil is an artistic creation, emphasizing human reflection on God. It was a practical choice for builders, filling window spaces while conveying faith. The trefoil’s elegance made it a lasting symbol in Catholic art. It invites contemplation of the Trinity’s unity and diversity.

The Triangle Within a Circle: Eternity and Unity

A triangle enclosed in a circle is a less common but meaningful Trinity symbol. The triangle’s three sides represent the three Persons, while the circle signifies God’s eternity. This combination reflects the teaching that the Trinity is both distinct and infinite (CCC 253). The symbol appeared in early Christian art and later in alchemical contexts before being reclaimed by the Church. Its simplicity conveys the balance of unity and distinction. The circle, with no beginning or end, aligns with descriptions of God in Revelation 1:8. Medieval artists used it to frame Trinitarian images or as a standalone emblem. Though not as widespread as the Shield of the Trinity, it offers a clear theological message. The triangle within a circle invites believers to ponder God’s timeless nature. It remains a subtle yet profound symbol in Catholic heritage.

The Three Fish: An Early Christian Emblem

Three interlocking fish forming a triangle or circle emerged as an early Christian symbol. The fish was a common sign of Christ, based on the Greek word ichthys (fish), an acronym for “Jesus Christ, Son of God, Savior.” When depicted as three, it represents the Trinity. Each fish stands for one Person, united in a single design. This symbol appeared in catacombs and on seals in the first centuries of Christianity. Its connection to Matthew 4:19—where Jesus calls disciples as “fishers of men”—adds depth. The three fish emphasize the Trinity’s role in salvation history. Unlike more abstract symbols, it ties directly to scripture and early practice. Its simplicity suited a persecuted Church needing discreet signs. The three fish remain a rare but authentic Trinitarian image.

The Triple Alpha: A Coded Testimony

In the Roman catacombs, archaeologists found graffiti with three Greek alphas (AAA) linked together. This “triple alpha” symbolized the Trinity in the early Church. The alpha, the first letter of the Greek alphabet, recalls Revelation 1:8, where God is “the Alpha and the Omega.” Three alphas together affirm one God in three Persons. This code was likely used by persecuted Christians to profess their faith discreetly. Scholar Margherita Guarducci documented its presence in 1st-century catacombs, predating formal creeds. The symbol’s subtlety made it a powerful witness under Roman rule. It shows how early believers expressed complex theology simply. Though not widely used today, the triple alpha reflects the Trinity’s ancient roots. It stands as a testament to the faith’s resilience.

The Interlaced Triangle and Trefoil: A Rare Variant

A triangle interlaced with a trefoil is a rare symbol of the Trinity. It combines the triangle’s three sides with the trefoil’s three lobes, creating a complex design. The interlacing suggests the eternal relationship among the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. This symbol appeared in medieval art, often in manuscripts or carvings. Its rarity may stem from its intricate construction, less suited to mass reproduction. The design emphasizes God’s divine eternity alongside Trinitarian distinction. It builds on simpler symbols, offering a layered theological statement. Few examples survive, but they show the creativity of Catholic artists. The interlaced triangle and trefoil invites deeper reflection on the Trinity. It remains a hidden gem in the Church’s symbolic tradition.

The Three-Leaf Clover: St. Patrick’s Legacy

Though better known, the three-leaf clover deserves mention for its historical role. Tradition credits St. Patrick with using it in 5th-century Ireland to explain the Trinity. The single leaf with three parts mirrors one God in three Persons. Its natural form made it relatable to rural converts. The clover’s unity reflects the divine essence shared by Father, Son, and Holy Spirit (CCC 254). While not as obscure as others, its origins are ancient and tied to evangelization. Depictions of St. Patrick often show him holding a clover, reinforcing its use. The symbol’s simplicity ensured its lasting impact. It remains a staple in catechesis, especially for children. The three-leaf clover bridges nature and theology in Catholic teaching.

The Circle of Three: A Universal Image

Three entwined circles, distinct yet unified, form another Trinity symbol. Each circle represents a Person, while their overlap shows their shared nature. The design echoes the Borromean Rings but is simpler, focusing on circular unity. Circles symbolize eternity in many cultures, aligning with God’s infinite being. This symbol appeared in early Christian art and later in heraldry. Its clarity makes it a versatile teaching tool. The three circles emphasize that no Person exists apart from the others. It reflects the relational aspect of the Trinity, as taught in CCC 255. Though less elaborate than the Shield of the Trinity, it conveys the same truth. The circle of three offers a timeless image of God’s unity.

The Hand, Fish, and Dove: A Combined Symbol

Some medieval art combined a hand, fish, and dove within a triangle to represent the Trinity. The hand signifies the Father as Creator, the fish the Son as Savior, and the dove the Holy Spirit, as in Matthew 3:16. The triangle unifies these distinct images. This composite symbol was rare but appeared in church decorations. It draws from scripture and tradition to illustrate each Person’s role. The hand recalls God’s power in Genesis 1, the fish ties to Christ’s mission, and the dove marks the Spirit’s presence. The combination offers a narrative of the Trinity’s work in salvation. Its complexity limited its use, but it enriched catechetical art. This symbol shows how Catholics linked theology to visual expression. It remains a unique example of Trinitarian symbolism.

The Role of Symbols in Catechesis

These ancient symbols were not just artistic flourishes but vital for teaching the faith. In an era before widespread literacy, visual aids conveyed complex doctrines. The Trinity, as a mystery (CCC 234), needed concrete images to reach believers. Symbols like the Shield of the Trinity or triquetra broke down abstract ideas into accessible forms. They also reinforced the Church’s unity across cultures, adapting local signs to Christian truths. Early catechists, like St. Patrick, used them to evangelize effectively. The variety of symbols shows the Church’s flexibility in communication. They invited contemplation, not just explanation, of God’s nature. Today, they remind Catholics of their rich heritage. These tools continue to aid understanding of the Trinity.

Theological Foundations of Trinitarian Symbols

Catholic theology underpins these symbols, rooted in scripture and tradition. The Trinity is revealed in events like Christ’s baptism (Matthew 3:16-17), where all three Persons appear. The Church Fathers, such as Tertullian, who coined “Trinity” around 190 AD, clarified this doctrine. Symbols reflect their insights, balancing unity and distinction. The Nicene Creed, formalized in 325 AD, affirms one God in three Persons, guiding symbolic development. Each symbol aligns with this creed, avoiding heresy like tritheism (three gods). The Catechism (CCC 237) notes traces of the Trinity in creation, which symbols often echo. They are not arbitrary but express revealed truth. This theological grounding ensures their accuracy. Ancient symbols thus remain reliable witnesses to Catholic belief.

Cultural Influences on Trinitarian Symbols

The Church often adopted symbols from surrounding cultures, giving them Christian meaning. The triquetra’s Celtic origins and the fleur-de-lis’s French ties show this adaptation. Early Christians avoided human depictions of God, favoring geometric forms. This practice respected Jewish tradition while engaging new converts. The vesica piscis and three fish drew from Greco-Roman art, familiar to early believers. Such borrowing made the faith approachable without compromising doctrine. The Borromean Rings, though later, reflect medieval interest in mathematics and unity. These cultural roots enriched Catholic symbolism. They demonstrate the Church’s ability to speak in local languages. This adaptability helped spread Trinitarian teaching worldwide.

Why These Symbols Matter Today

Modern Catholics may not encounter these symbols often, yet they hold value. They connect believers to the early Church, showing continuity of faith. Understanding them deepens appreciation for the Trinity’s complexity. In a visual age, they offer alternatives to verbal explanations. They also counter misunderstandings, like viewing the Trinity as three gods. Studying them fosters historical and theological literacy. These symbols can inspire art, prayer, and education today. They remind Catholics that faith engages both mind and imagination. Preserving them honors the creativity of past generations. They remain a quiet testimony to God’s triune nature.

Challenges in Interpreting Ancient Symbols

Interpreting these symbols today poses difficulties due to their age and context. Some, like the triquetra, have pre-Christian origins, raising questions about intent. Others, like the triple alpha, rely on archaeological evidence that may be incomplete. Medieval art often blended meanings, complicating analysis. Modern viewers may miss nuances without historical knowledge. The Church’s adaptation of pagan symbols can confuse their Christian purpose. Yet, these challenges do not diminish their validity. Scholarly study clarifies their use in Catholic tradition. Approaching them with humility avoids misreading. They still speak to the Trinity’s truth when understood properly.

Conclusion: A Legacy of Faith

These ancient symbols of the Trinity reveal the Church’s effort to express an inexpressible mystery. From the Shield of the Trinity to the three-leaf clover, each offers a unique perspective. They blend theology, art, and culture into a rich tradition. Their variety reflects the depth of Catholic thought over centuries. They served practical purposes, teaching the faithful in diverse settings. Today, they invite Catholics to explore their heritage. Though less familiar, they remain relevant for study and prayer. The Trinity, as the central mystery of faith (CCC 234), shines through these enduring signs. They testify to a God who is one yet three, eternal yet present. This legacy continues to shape Catholic identity and devotion.