Brief Overview

- The process of electing a pope, known as a conclave, has a long history in the Catholic Church, shaped by centuries of tradition and reform.

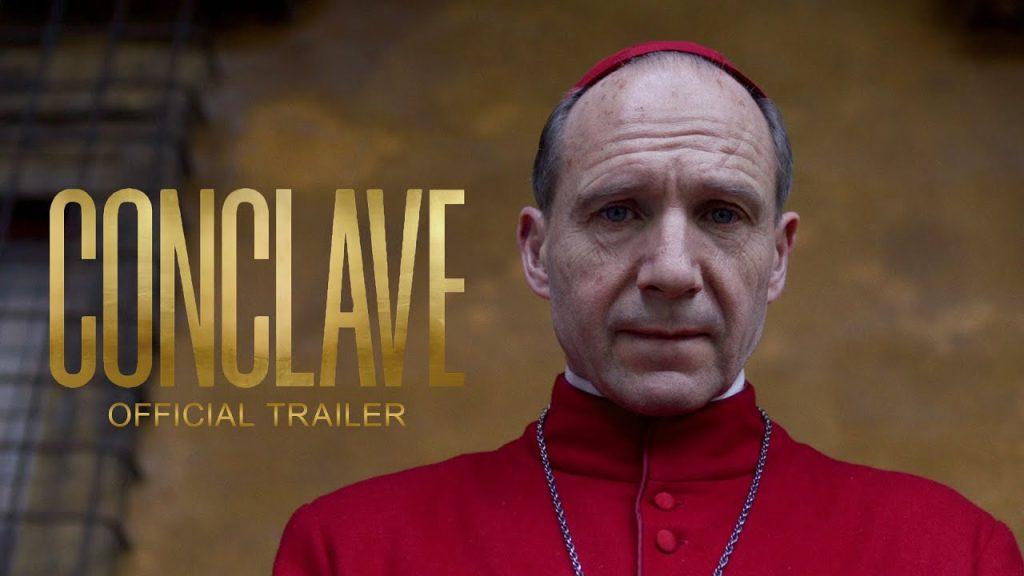

- The 2024 film Conclave, directed by Edward Berger, offers a fictional take on this process, focusing on intrigue and drama among cardinals.

- Historically, conclaves evolved from informal elections to a formalized system restricted to cardinals, often under strict rules of seclusion.

- While the film captures some procedural aspects, it amplifies tensions and introduces fictional elements not aligned with Church practice.

- Catholic teaching and historical records provide a clear framework for conclaves, rooted in faith and governance rather than suspense.

- This article examines the real conclave process and contrasts it with the cinematic portrayal in Conclave.

Detailed Response

Historical Evolution of the Conclave

The origins of the papal election process date back to the early Church, when bishops were chosen by a combination of clergy and laity in Rome. Over time, this practice became more defined as the Church grew in structure and influence. By the 11th century, the selection of the pope was increasingly limited to the clergy of Rome, particularly the cardinals, who were seen as the senior leaders of the Church. Secular rulers, such as emperors and kings, often interfered in these elections, leading to disputes and delays. The Second Lateran Council in 1139 established a key reform, requiring a two-thirds majority of cardinals to elect a pope, a rule that remains in place today. This shift aimed to ensure a clearer and more unified decision-making process. The term “conclave” emerged later, tied to the practice of locking cardinals together until a pope was chosen. This practice was formalized in the 13th century to address prolonged vacancies and external pressures. The decree Ubi periculum from 1274, issued by Pope Gregory X, set the stage for the modern conclave by mandating seclusion and strict voting procedures. In contrast, the film Conclave simplifies this history, focusing instead on a condensed, dramatic version of events.

The Role of Ubi Periculum in Shaping Modern Conclaves

The Ubi periculum decree of 1274 was a response to a crisis following the death of Pope Clement IV in 1268, when cardinals took nearly three years to elect a successor. This delay frustrated the faithful and exposed the Church to political manipulation. Pope Gregory X, elected after this ordeal, introduced rules to prevent such situations in the future. Cardinals were to be locked in a single location, with limited food and comforts, until they reached a decision. The decree required a two-thirds majority and imposed penalties for delay, such as reduced rations after several days. These measures were practical, aimed at ensuring a swift and focused election. Over time, the Church refined these rules, but the core principle of seclusion remained. The term “cum clave” (with a key) reflects this locking-in practice, which became a hallmark of the conclave. The film Conclave nods to this seclusion but exaggerates it into a setting of constant tension and conspiracy. In reality, the process, while serious, is guided by prayer and deliberation, not theatrical standoffs.

Key Features of a Modern Conclave

Today, the conclave follows a detailed set of rules outlined in documents like Universi Dominici Gregis, issued by Pope John Paul II in 1996 and amended by later popes. It begins after the death or resignation of a pope, with cardinals under the age of 80 gathering in Vatican City. The process takes place in the Sistine Chapel, where cardinals are secluded from the outside world. They vote up to four times a day, with ballots burned after each round—black smoke signals no decision, white smoke indicates a new pope. A two-thirds majority is still required, though adjustments can be made if voting stalls. The cardinals swear oaths of secrecy and fidelity to the process, emphasizing its sacred nature. Preparations include sweeping the area for electronic devices to ensure privacy. The film Conclave accurately depicts the Sistine Chapel setting and smoke signals but adds fictional layers of intrigue, such as hidden agendas driving every vote. In practice, the conclave is a structured event, not a free-for-all power struggle. Refer to Universi Dominici Gregis for the full procedural framework.

The Role of Cardinals in the Conclave

Cardinals eligible to vote, known as electors, are those under 80 years old at the start of the conclave, typically numbering around 120, though the exact count varies. They represent the global Church, coming from diverse regions and backgrounds. Their primary task is to discern the will of God in selecting a pope, a responsibility they approach through prayer and discussion. Before voting begins, they attend General Congregations to assess the Church’s needs and potential candidates. Once inside the conclave, they are isolated, with no access to phones, internet, or outside news. Each cardinal writes a name on a ballot, folds it, and places it in a chalice, a simple yet solemn act. The process is overseen by designated officials, including a scrutineer and infirmarian for sick cardinals. The film Conclave portrays cardinals as deeply divided and scheming, which exaggerates their human flaws over their shared mission. Historical records show that while debates occur, unity in faith guides their decisions. The Catechism of the Catholic Church (CCC 882) underscores the pope’s role, which the cardinals seek to uphold.

Secrecy and Solemnity in the Conclave

Secrecy is a cornerstone of the conclave, intended to protect the integrity of the election and the freedom of the cardinals’ choices. Participants take a solemn oath not to reveal discussions or votes, even after the conclave ends. This rule dates back centuries, reflecting the Church’s desire to shield the process from external influence. Violations of secrecy can lead to excommunication, a penalty rooted in canon law. The Sistine Chapel is secured, with modern technology like signal jammers used to prevent leaks. The burning of ballots, a tradition tied to the smoke signals, ensures no records remain. This secrecy fosters an environment of prayerful focus rather than political maneuvering. In Conclave, secrecy becomes a plot device for suspense, with breaches and betrayals driving the story. Real conclaves, however, prioritize confidentiality as a sacred duty, not a source of drama. The film’s depiction strays from the Church’s emphasis on trust and obedience.

The Spiritual Dimension of the Conclave

For the Catholic Church, the conclave is not merely a political exercise but a spiritual event guided by the Holy Spirit. Cardinals begin with a Mass invoking divine guidance, known as the Missa Pro Eligendo Romano Pontifice. They enter the Sistine Chapel under Michelangelo’s Last Judgment, a visual reminder of their accountability to God. Voting is interspersed with prayers and reflections, grounding the process in faith. The Church teaches that the Holy Spirit assists in the selection, a belief articulated in Acts 1:26 and centuries of tradition. While human factors like experience and theology influence votes, the spiritual lens shapes the cardinals’ approach. The film Conclave largely omits this dimension, focusing instead on human ambition and conflict. In reality, the conclave balances practical governance with reliance on divine will. The Catechism (CCC 153-155) highlights the role of providence, which underpins this process. The cinematic version misses this core Catholic perspective.

The Film’s Portrayal of Conclave Procedure

In Conclave, Edward Berger crafts a narrative where the election unfolds over a few tense days, marked by rapid twists and revelations. The Sistine Chapel is shown as a claustrophobic stage for rival factions among the cardinals. Voting scenes include accurate details, like the ballot chalice and smoke signals, but the pace is accelerated for effect. The film introduces a fictional cardinal protagonist managing crises, a role that does not exist in real conclaves. Historical procedures, such as the scrutiny of ballots, are simplified or dramatized to heighten suspense. Real conclaves can last days or weeks, with a slower, more methodical rhythm. The film also suggests external interference, which modern security measures make unlikely. While engaging, this portrayal sacrifices accuracy for storytelling. Audiences see a thriller, not a reflection of the Church’s careful process. The contrast lies in purpose: the film entertains, while the conclave serves a higher calling.

Fictional Additions in “Conclave”

The movie Conclave invents several elements absent from real papal elections. A central plot involves a surprise candidate emerging late in the process, a twist that stretches credibility given the pre-conclave discussions among cardinals. It also depicts a scandal uncovered mid-voting, halting the proceedings—an event without historical precedent in modern times. The film’s cardinals engage in overt campaigning, which contradicts the conclave’s ban on such behavior. Another addition is the exaggerated role of a single cardinal orchestrating the outcome, undermining the collective nature of the process. Real conclaves rely on consensus, not individual heroics. The film’s use of a terrorist attack as a backdrop further departs from reality, adding external chaos the Church works to avoid. These choices reflect cinematic license, not Catholic practice. They create a gripping story but misrepresent the conclave’s structure and spirit. Historical records, like those of the 2013 conclave, show a more orderly reality.

Historical Accuracy vs. Cinematic License

While Conclave draws on real elements—like the Sistine Chapel and the two-thirds majority—it prioritizes drama over fidelity to history. Past conclaves, such as the 2005 election of Benedict XVI, followed a predictable sequence without the film’s upheavals. The movie condenses complex traditions into a streamlined narrative, omitting the preparatory phase of General Congregations. It also amplifies personal rivalries, whereas real cardinals operate under a shared commitment to the Church. Historical disruptions, like the 1799-1800 conclave during Napoleon’s influence, were external, not internal as in the film. Modern conclaves benefit from clear rules and security, reducing the chaos Conclave portrays. The film’s timeline, with rapid votes and resolutions, ignores the deliberate pace of actual elections. Berger’s work is art, not a documentary, and should be judged as such. Still, it risks misleading viewers about the conclave’s nature. For a factual account, see Vatican archives on past elections.

The Conclave’s Purpose in Catholic Teaching

The conclave exists to ensure the continuity of the Church’s leadership, a role tied to Christ’s commission to Peter in Matthew 16:18-19. The pope, as bishop of Rome, holds a unique office uniting the faithful, as noted in CCC 882-883. Cardinals act as stewards of this mission, selecting a leader to guide the Church in faith and morals. The process reflects the Church’s hierarchical structure, balancing human input with divine guidance. It is not a democratic election but a discernment rooted in tradition. The film Conclave frames the election as a power struggle, missing its deeper purpose. In Catholic teaching, the pope’s authority serves the truth, not personal gain. The conclave’s design—seclusion, prayer, majority rule—supports this goal. Historical reforms aimed to protect this mission from worldly interference. The cinematic version, while compelling, overlooks this theological foundation.

Public Perception and the Conclave

The secrecy of the conclave often fuels curiosity and speculation among the public, a dynamic Conclave exploits for its plot. In reality, the Church limits information to maintain focus on the spiritual task, not to hide intrigue. The smoke signals—black for no decision, white for a new pope—are the primary public signs, a tradition dating back centuries. Media coverage of modern conclaves, like that of 2013, provides factual updates without the drama of Berger’s film. Catholics view the process as a sacred duty, not a spectacle. The film’s conspiracies tap into secular fascination with Vatican secrecy, but they distort the reality. Historical conclaves faced scrutiny, yet their outcomes shaped the Church stably. The movie caters to an audience expecting twists, not the faithful seeking clarity. It reflects cultural trends more than Catholic practice. The Church addresses this gap through official statements post-election.

The Real Conclave’s Pace and Deliberation

Actual conclaves proceed at a measured pace, allowing cardinals time to reflect and pray between votes. The 2013 conclave, electing Pope Francis, took two days and five ballots, a typical duration. Rules permit up to four voting rounds daily, with breaks if no pope is chosen after several days. This structure prevents haste and encourages consensus. The film Conclave compresses this into a frantic sprint, with decisions unfolding in hours. Real cardinals deliberate over the Church’s global needs—missions, doctrine, unity—not personal agendas. Historical examples, like the 1978 conclaves, show steady progress, not chaos. The film’s rapid-fire conflicts serve its runtime, not reality. Vatican documentation, such as post-conclave reports, confirms this slower rhythm. The difference highlights the Church’s priority: a thoughtful choice, not a race.

Security Measures in Modern Conclaves

Modern conclaves employ strict security to preserve secrecy and independence, a detail Conclave twists into suspense. The Sistine Chapel is swept for bugs, and electronic devices are banned. External contact is limited to emergencies, handled by designated officials. These precautions evolved from past interference, like the vetoes of monarchs in earlier centuries. Today, Vatican staff ensure cardinals remain isolated, with jammed signals blocking communication. The film’s breaches—leaked secrets, outside threats—contradict this reality. Historical conclaves lacked such safeguards, but modern ones prioritize control. The Church sees this as protecting the process’s integrity, not creating mystery. Conclave uses security as a plot point, not a safeguard. Refer to Universi Dominici Gregis for current protocols.

Faith vs. Fiction in Depicting the Conclave

The Catholic Church views the conclave as an act of faith, trusting the Holy Spirit to guide the outcome, as in John 16:13. Cardinals are human, with biases and preferences, but their oaths bind them to a higher purpose. The film Conclave reduces this to a secular contest, stripping away the spiritual core. Real conclaves blend practicality—voting, counting—with reliance on prayer. Historical accounts, like Cardinal Ratzinger’s 2005 election, emphasize this balance. The movie’s focus on betrayal and ambition reflects a worldview foreign to Catholic teaching. Faith shapes the process, not fiction’s need for conflict. The Catechism (CCC 190-191) frames such events as guided by providence. Berger’s narrative entertains but misses this truth. The gap reveals the challenge of portraying sacred acts in secular art.

The Conclave’s Outcome and Announcement

Once a pope is elected, he is asked if he accepts, chooses a name, and prepares to appear publicly, a moment called Habemus Papam. This follows days of voting and reflection, not the film’s rushed climax. The new pope dons white vestments and greets the faithful from St. Peter’s balcony. In 2013, Pope Francis followed this tradition, marking a simple transition. The film Conclave ends with a dramatic reveal, but real announcements are straightforward. Cardinals’ ballots are burned with chemicals for white smoke, signaling success. Historical conclaves varied in length, but the outcome is always clear: a new leader. The movie’s twist—uncertainty lingering—defies this certainty. Catholic practice ensures closure, not ambiguity. The faithful celebrate the result as God’s will, not a cliffhanger.

Comparing Conclave Lengths Historically

Conclave durations have varied widely, offering context for the film’s compressed timeline. The longest, from 1268-1271, prompted Ubi periculum, lasting nearly three years. Modern conclaves are shorter—2005 took two days, 1978’s second took three. The average since 1900 is about three days, reflecting streamlined rules. The film Conclave squeezes this into a single, intense span, ignoring historical norms. Real delays stem from deliberation, not drama. The Church values a thorough process over speed, as seen in Vatican records. Berger’s version sacrifices this for pacing, a creative choice. Historical data shows consistency, not the film’s volatility. The contrast underscores reality’s patience versus fiction’s urgency.

The Film’s Appeal and Catholic Response

Conclave appeals to audiences through suspense and strong performances, earning praise as a thriller. Its Catholic setting draws interest, but the Church sees it as entertainment, not education. Official responses, like Vatican News critiques, often note such works’ divergence from truth. The faithful are encouraged to seek facts in Church teachings, like CCC 880-887. The film’s success lies in its craft, not its accuracy. Real conclaves lack the glamour of cinema but hold deeper meaning for Catholics. Berger’s vision reflects human creativity, not divine order. The Church counters with clarity, not condemnation. History and doctrine provide the true story. Fiction entertains; faith sustains.

Conclusion: Reality Over Representation

The real conclave is a meticulous, faith-driven process, far from Conclave’s cinematic lens. It blends tradition, prayer, and governance to select a pope, as seen in centuries of practice. The film offers a compelling tale but trades accuracy for excitement. Historical reforms like Ubi periculum shaped a system of order, not chaos. Modern rules ensure seclusion and deliberation, not conspiracy. Catholics see the Holy Spirit at work, a dimension the movie ignores. Both versions engage—fiction through story, reality through purpose. The Church’s process withstands scrutiny; the film’s does not. For truth, look to Vatican records, not the screen. The difference is stark: one serves faith, the other fiction.