Brief Overview

- Sola Scriptura, or “Scripture alone,” is the belief that the Bible is the sole infallible authority for Christian faith and practice.

- This doctrine emerged during the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century as a response to perceived errors in Church tradition.

- Catholic teaching, however, holds that both Scripture and Sacred Tradition together form the foundation of Christian truth.

- The question of whether Sola Scriptura is reasonable requires examining its basis in Scripture and history.

- Evidence from early Christianity suggests a reliance on both written and oral sources of authority.

- This article explores these issues to provide a clear Catholic perspective on the matter.

Detailed Response

The Meaning of Sola Scriptura

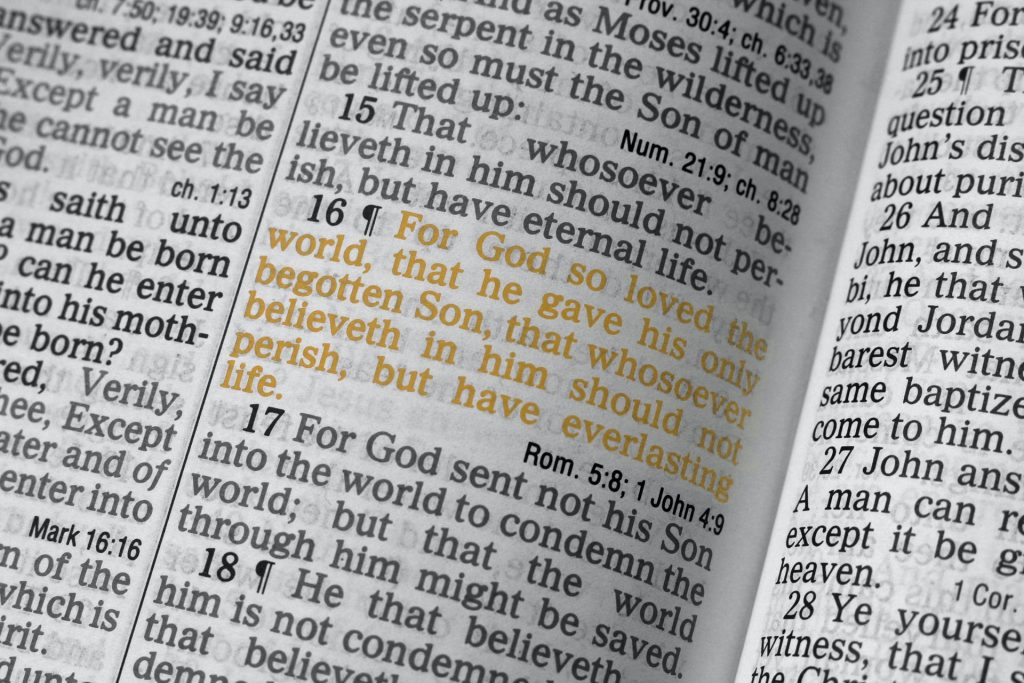

Sola Scriptura asserts that the Bible alone is sufficient for determining Christian doctrine and practice. This idea was championed by reformers like Martin Luther in the 1500s. They argued that Church traditions had strayed from biblical truth over time. According to this view, Scripture is self-sufficient and needs no additional authority to interpret or supplement it. The doctrine assumes that the Bible contains all necessary teachings for salvation. It also implies that individual believers can interpret it without an authoritative guide. However, this raises questions about consistency and unity in belief. If Scripture alone is the rule, why do Protestant groups differ widely in their teachings? The Catholic Church challenges this notion by pointing to the Bible’s own testimony. No passage explicitly states that Scripture alone is the complete rule of faith.

Scripture’s Silence on Sola Scriptura

A key issue with Sola Scriptura is that the Bible does not teach it. Nowhere in its pages is there a command to rely solely on written texts. Instead, Scripture often points to other sources of authority. For example, in 2 Thessalonians 2:15, Paul instructs believers to hold fast to traditions taught “by word of mouth or by letter.” This suggests a dual reliance on oral and written teaching. The absence of a verse endorsing Scripture alone is significant. If Sola Scriptura were foundational, one would expect a clear directive. Yet, the Bible assumes a broader context for understanding God’s revelation. Catholic teaching aligns with this, emphasizing both Scripture and Tradition. The lack of scriptural support undermines the reasonableness of Sola Scriptura.

The Role of Oral Tradition in Scripture

Scripture itself highlights the importance of oral tradition. In 1 Corinthians 11:2, Paul praises the Corinthians for maintaining the traditions he delivered to them. Similarly, 2 Thessalonians 3:6 urges believers to follow the tradition received from the apostles. These passages show that early Christians valued teachings passed down orally. This was not a temporary measure but an ongoing practice. In Philippians 4:9, Paul tells the Philippians to practice what they learned and received from him, including what they saw and heard. This indicates that Christian truth was not limited to written texts. The Bible reflects a living faith transmitted through multiple channels. Catholic doctrine preserves this balance between Scripture and Tradition. Relying solely on Scripture ignores this biblical evidence.

The Canon of Scripture and Tradition

The Bible does not list its own contents. No verse specifies which books belong in the New Testament. This poses a problem for Sola Scriptura, as the canon’s authority must come from outside Scripture. Historically, the Church determined the canon at councils like Carthage in 397 A.D. These decisions relied on Tradition, not a divine table of contents within the Bible. Early Christians used many writings, some of which claimed inspiration, like the Apocalypse of Peter. Yet, only certain books were selected as inspired. This process required discernment guided by apostolic tradition. The Catechism of the Catholic Church (CCC 120) affirms this role of Tradition in establishing the canon. Thus, Scripture’s very existence depends on Tradition, challenging Sola Scriptura’s premise.

Inspiration and Authority of New Testament Books

No New Testament book explicitly claims to be divinely inspired. While Ephesians 3:3 speaks of revelation, similar claims appear in non-canonical texts. For instance, the Protoevangelium of James also references divine insight. This raises the question: how do we know which books are inspired? The answer lies in the Church’s authority, rooted in Tradition. Early Christians did not rely on self-evident inspiration within the texts. Instead, they trusted the apostolic witness passed down orally and in writing. The Council of Carthage formalized this in 397 A.D., long after the books were written. Catholic teaching sees this as evidence of Tradition’s necessity (CCC 111). Sola Scriptura cannot account for this without appealing to an external authority.

Early Evidence of Oral Tradition

Oral tradition predates much of the New Testament. By A.D. 90, writings like 1 Clement show its influence. This letter, written by Clement of Rome, addresses the Corinthian church. It mentions Peter and Paul’s ministries in Rome, a detail not found in Scripture. It also discusses apostolic succession and the Eucharist as a sacrifice. These teachings were accepted by early Christians, even though 1 Clement was later excluded from the canon. At the time, it was widely regarded as authoritative. This shows that oral tradition shaped Christian belief alongside Scripture. The Catechism (CCC 76) notes that Tradition preserves apostolic teaching. Sola Scriptura overlooks this early reliance on oral sources.

Peter and Paul in Rome

1 Clement provides evidence of Peter and Paul’s presence in Rome. It describes their martyrdoms and ministries, details absent from the New Testament. This information was part of oral tradition by A.D. 90. Clement, a contemporary of the apostles, wrote with authority to the Corinthians. His letter assumes the church knew these facts. Later, Ignatius of Antioch confirms this tradition around A.D. 107. In his letter to the Romans, he references Peter and Paul as apostles. This consistency across regions shows a shared oral heritage. Catholic teaching accepts this as part of Sacred Tradition (CCC 83). Sola Scriptura cannot explain this without dismissing early testimony.

Apostolic Succession in Early Writings

Apostolic succession appears in 1 Clement as a principle of Church order. Clement writes that the apostles appointed bishops and provided for their successors. This ensured continuity of teaching and authority. Around A.D. 107, Ignatius of Antioch reinforces this in his letter to the Smyrnaeans. He instructs believers to follow the bishop as Christ follows the Father. This structure relies on oral tradition, not Scripture alone. The New Testament hints at succession, as in Acts 1:20-26, but does not fully define it. Tradition fills this gap, as noted in CCC 77. Early Christians saw this as essential to preserving truth. Sola Scriptura lacks a mechanism for such continuity.

The Eucharist as a Sacrifice

1 Clement describes the Eucharist as a sacrifice, echoing 1 Corinthians 10:16-22. This understanding dates to A.D. 90, when Clement wrote. He ties it to appointed times and priests, suggesting a liturgical tradition. Ignatius, writing later, calls the Eucharist the flesh of Christ, offered on an altar. This aligns with Paul’s teaching in 1 Corinthians 11:23-25. The early Church saw the Eucharist as more than a symbol. This belief came from oral tradition, not just Scripture. The Catechism (CCC 1356) affirms this sacrificial view. Sola Scriptura struggles to account for this consistent early practice. It risks reducing the Eucharist to a mere memorial.

Continuity of Tradition in the Early Church

Clement and Ignatius, both linked to apostles, taught from Scripture and Tradition. Clement worked with Paul (Philippians 4:3), while Ignatius knew John. Their writings reflect a unified tradition across regions. This tradition shaped the Church’s doctrine and worship. It also preserved the New Testament texts we have today. Bishops, as successors to the apostles, guarded this heritage. The Catechism (CCC 78) explains Tradition’s role in maintaining apostolic faith. Sola Scriptura dismisses this continuity, relying only on written texts. Yet, the Bible emerged from a Church living both sources. This dual foundation questions the doctrine’s reasonableness.

Tradition Among the Jews

Jewish practice before Christ combined Scripture and oral tradition. The Old Testament does not contain all Jewish beliefs. For example, the “chair of Moses” in Matthew 23:2-3 comes from tradition, not Scripture. Jesus upholds this authority, telling followers to obey the Pharisees. Ancient Jewish texts, like the Midrash, confirm this tradition. It symbolized teaching authority passed from Moses. This was not written in the Torah but was widely accepted. Jesus’ acceptance shows tradition’s legitimacy. Catholic teaching sees this as a precedent for Christian Tradition (CCC 83). Sola Scriptura cannot reconcile this with its rejection of oral authority.

Jesus and Oral Tradition

Jesus lived within Jewish oral traditions. In Matthew 23:2-3, He endorses the “chair of Moses” as authoritative. This concept is absent from the Old Testament. Yet, He treats it as valid, showing respect for tradition. His teachings often assume unwritten customs. For instance, His debates with Pharisees reflect shared oral knowledge. This suggests that divine truth includes more than Scripture. The Catechism (CCC 82) notes that Christ entrusted His message to the apostles orally. Sola Scriptura ignores this, limiting revelation to the written word. Jesus’ example challenges its exclusivity.

Extra-Scriptural Traditions in the New Testament

The New Testament cites traditions outside the Old Testament. In 1 Corinthians 10:4, Paul says a rock followed the Israelites, a detail from Jewish lore. Jude 9 mentions Michael and Satan disputing over Moses’ body, not found in Scripture. Jude 14 quotes Enoch, another extra-biblical source. In 2 Timothy 3:8, Paul names Pharaoh’s magicians, unnamed in Exodus. These references show reliance on oral tradition. The apostles used it to interpret and teach. Catholic doctrine accepts this interplay (CCC 80). Sola Scriptura cannot explain these without admitting external influence. This weakens its claim to sufficiency.

The Holy Spirit’s Guidance

Early Church leaders believed the Holy Spirit guided them. In John 14:26, Jesus promises the Spirit will teach and remind the apostles. John 16:13 says the Spirit will guide into all truth. This promise extends beyond the apostles to the Church (John 17:20-21). The Spirit ensures continuity of teaching. Bishops saw themselves as stewards of this guidance. The Catechism (CCC 86) ties this to Tradition’s role. Sola Scriptura attributes authority to Scripture alone, not the Spirit-led Church. Yet, Scripture credits the Spirit with preserving truth. This supports a broader view of revelation.

The Church as Pillar of Truth

In 1 Timothy 3:15, the Church is called the “pillar and foundation of truth.” Scripture never claims this role for itself. The Church, guided by the Spirit, interprets and upholds truth. This aligns with 2 Peter 1:20-21, which warns against private interpretation. Early bishops relied on this authority to define the canon. Tradition and Scripture together formed their rule of faith. The Catechism (CCC 85) affirms the Church’s teaching office. Sola Scriptura separates Scripture from this context. It risks fragmenting truth without a unifying authority. The Bible supports the Church’s role over Scripture alone.

The Canon’s Dependence on the Church

The New Testament canon was set by the Church, not Scripture. Councils like Carthage in 397 A.D. finalized it. This process used Tradition to discern inspired texts. Jewish leaders similarly shaped the Old Testament canon. Jesus upheld their authority in Matthew 23:2-3. The Spirit guided both efforts, as promised in John 16:13. The Catechism (CCC 120) credits the Church with this task. Sola Scriptura assumes the Bible’s authority is self-evident. Yet, its formation proves otherwise. The Church precedes and authenticates Scripture.

Tradition’s Ongoing Role

Christian truth is not static but preserved dynamically. The apostles’ revelation is complete, but its understanding grows. The Spirit guides this, as in John 14:26. Tradition ensures fidelity to the original message. Bishops, as successors, maintain this continuity. The Catechism (CCC 94) describes this living transmission. Sola Scriptura sees truth as fixed in text alone. This ignores the Spirit’s role in the Church. Scripture and Tradition together keep the faith alive. This balance refutes a solely scriptural approach.

Unity of Scripture and Tradition

Catholic teaching unites Scripture and Tradition as one deposit of faith. 2 Thessalonians 2:15 reflects this dual source. The early Church lived this unity, as seen in Clement and Ignatius. The canon itself emerged from it. The Spirit sustains both, per John 16:13. The Catechism (CCC 78) explains their interdependence. Sola Scriptura splits them, prioritizing Scripture. This contradicts biblical and historical evidence. Truth requires both, not one alone. This unity is more reasonable than Sola Scriptura.

Historical Rejection of Sola Scriptura

The early Church never embraced Sola Scriptura. From Clement to the councils, Tradition was integral. Bishops fought heresies using both Scripture and oral teaching. The canon’s formation proves this reliance. No early text advocates Scripture alone. Protestantism introduced this idea centuries later. Catholic doctrine preserves the original practice (CCC 83). Sola Scriptura lacks historical roots in Christianity’s first 1,500 years. It appears as an innovation, not a restoration. This weakens its claim to reasonableness.

Conclusion: A Reasonable Alternative

Sola Scriptura is not reasonable given Scripture’s silence on it. The Bible supports Tradition alongside written texts. Early Christians relied on both, as seen in 1 Clement and Ignatius. The canon itself depends on Church authority, guided by the Spirit. Jesus and the apostles used oral tradition, per Matthew 23:2-3 and Jude 9. The Church, as 1 Timothy 3:15 states, upholds truth. Catholic teaching offers a consistent alternative. It honors Scripture within its historical context. Tradition complements it, ensuring unity and fidelity. This dual approach aligns with reason, history, and faith.