Brief Overview

- The Catholic Church teaches that salvation is a gift from God, received through faith and expressed in works of charity.

- This belief contrasts with some Protestant views that emphasize salvation by faith alone, apart from works.

- Catholic doctrine holds that faith and works are inseparable, both being necessary for a living relationship with God.

- Scripture, tradition, and Church teaching form the basis for this understanding, offering a balanced perspective on human cooperation with divine grace.

- The Catechism of the Catholic Church provides clear guidance on how faith and works interact in the life of a believer.

- This article explores these teachings, addressing common questions and clarifying the Catholic position.

Detailed Response

The Foundation of Catholic Teaching on Salvation

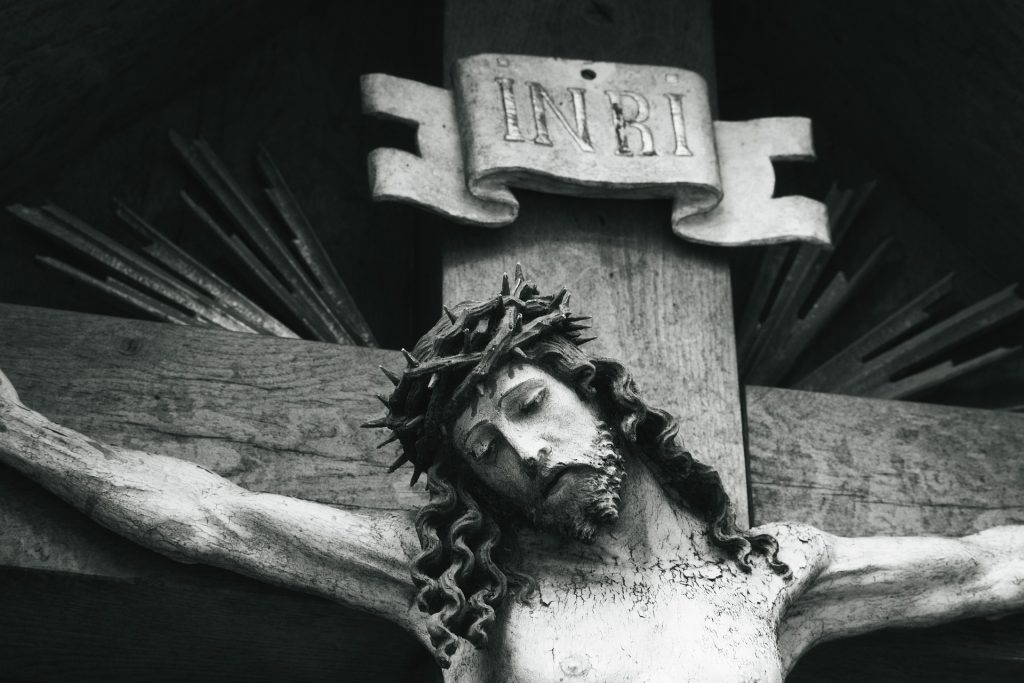

The Catholic Church has long taught that salvation is a gift from God, freely given through His grace. This grace comes through Jesus Christ, whose life, death, and resurrection opened the way to eternal life. However, the Church emphasizes that humans must respond to this gift actively, not passively. Faith is the starting point, the initial acceptance of God’s love and truth. Yet, faith alone, without a corresponding change in behavior or action, is incomplete. The Church points to the necessity of works as a natural outgrowth of genuine faith. This teaching is rooted in scripture, interpreted through centuries of tradition. For instance, James 2:17 states that faith without works is dead, a key text for Catholic theology. The Church does not claim that humans earn salvation by their own efforts. Instead, it teaches that works are a cooperation with God’s grace, made possible by faith (see CCC 1996-2005).

This understanding reflects a holistic view of the human person. Faith is not merely intellectual assent to propositions about God. It involves the whole person—mind, heart, and will—leading to a life transformed by love. Works of charity, obedience, and virtue are the evidence of this transformation. The Church rejects the idea that good deeds can merit salvation apart from grace. Rather, they are the fruit of a faith that has been enlivened by God’s presence. This balance prevents two extremes: a reliance on works without faith, or a faith that claims no responsibility for action. Catholic teaching insists that both are essential, like two sides of the same coin. The writings of the early Church Fathers, such as Augustine, reinforce this view. They saw faith and works as intertwined in the process of justification (CCC 1987-1995).

Scripture and the Unity of Faith and Works

Scripture provides a strong foundation for the Catholic position on faith and works. The Letter of James is particularly clear in its insistence that faith must be active. James 2:24 explicitly states that a person is justified by works and not by faith alone. This passage has often been a point of contention with some Protestant interpretations. However, Catholics see it as consistent with the broader biblical message. For example, Matthew 25:31-46 describes the final judgment, where Jesus separates the sheep from the goats based on their actions toward the needy. These works—feeding the hungry, clothing the naked—are not optional extras but signs of a living faith. The Church interprets these texts as showing that love and action are integral to salvation. Paul’s writings, often cited for the “faith alone” view, are not in conflict when read in context. In Galatians 5:6, Paul speaks of “faith working through love,” aligning with Catholic doctrine (CCC 1814-1816).

The Gospels further illustrate this unity. Jesus frequently calls His followers to both believe and act. In John 14:15, He says, “If you love me, you will keep my commandments.” Obedience and love are tied to faith, not separate from it. The parable of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:25-37) shows that eternal life is linked to loving one’s neighbor in concrete ways. Catholic teaching does not view these actions as earning God’s favor. Instead, they are responses to the grace already received through faith. The Church emphasizes that scripture must be understood as a whole, not in isolated verses. This approach avoids reducing salvation to a single formula. It also respects the complexity of God’s plan for humanity. The interplay of faith and works is thus a recurring theme across the New Testament (CCC 1821).

The Role of Grace in Faith and Works

Grace is the cornerstone of Catholic teaching on salvation. Without it, neither faith nor works would be possible. The Church teaches that humans are incapable of saving themselves due to original sin. God’s grace, poured out through Christ, restores the ability to respond to Him. Faith is itself a gift, initiated by God, not a human achievement. Works, too, depend on grace, as they flow from a heart transformed by divine love. This is why the Church rejects the notion of “works righteousness”—the idea that good deeds alone can earn salvation. Instead, it speaks of merit as a secondary effect of grace (CCC 2006-2011). Humans cooperate with God, but He remains the source of all goodness. This cooperation is an act of freedom, not coercion.

The sacraments are a primary means of receiving this grace. Baptism, for instance, initiates a person into the life of faith. The Eucharist strengthens that faith and empowers believers to live it out. Confession restores grace when sin has damaged the relationship with God. These acts are not separate from faith but deepen it, enabling good works. The Church teaches that grace precedes, accompanies, and completes every step of the journey toward salvation. This dynamic interplay ensures that neither faith nor works can be isolated. The Council of Trent, responding to Reformation debates, clarified this point in the 16th century. It affirmed that justification involves both faith and works, sustained by grace. This teaching remains authoritative today (CCC 1999-2000).

Historical Context and the Reformation Debate

The question of faith and works became a central issue during the Protestant Reformation. Martin Luther and other reformers emphasized “sola fide,” or faith alone, as the means of justification. They reacted to perceived abuses in the Catholic Church, such as the sale of indulgences. These practices suggested that salvation could be bought or earned, distorting Church teaching. Luther argued that human works were irrelevant, pointing to Romans 3:28 for support. However, Catholic theologians countered that this view misread both scripture and tradition. The Council of Trent was convened to address these challenges. It rejected the idea that faith alone, without charity, was sufficient for salvation. The council upheld the necessity of works as an expression of faith, not a replacement for it. This response shaped the modern Catholic understanding (CCC 2010).

The debate revealed a difference in emphasis rather than a total opposition. Catholics agree that salvation is not earned by human effort alone. They also affirm that faith is the root of justification. However, they see works as the natural consequence of that faith, not an optional addition. The Reformation critique prompted the Church to clarify its teachings. Trent emphasized that grace is primary, but human cooperation is real. This clarification avoided extremes on both sides. Today, ecumenical dialogues with Protestant communities show growing agreement on these points. The Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification (1999) between Catholics and Lutherans is one example. It reflects a shared belief in grace, faith, and the Christian life (CCC 1987-1995).

Faith and Works in Daily Life

For Catholics, the doctrine of faith and works is not abstract but practical. It shapes how believers live each day. Faith begins with trust in God, expressed through prayer and worship. Yet, it extends to actions—helping the poor, forgiving others, and seeking justice. The Church teaches that these works are not burdens but opportunities to grow closer to God. They reflect the love that faith inspires. For example, the corporal works of mercy, like visiting the sick, are concrete expressions of belief. The spiritual works, such as instructing the ignorant, also flow from faith. This integration is a hallmark of Catholic spirituality. It calls believers to a life of active holiness (CCC 1822-1829).

The saints provide models of this balance. St. Teresa of Calcutta, known as Mother Teresa, combined deep faith with tireless service to the poor. Her belief in Christ’s presence in the suffering drove her actions. Similarly, St. Francis of Assisi lived a radical faith that led to radical works of charity. These examples show that faith and works are not in tension but in harmony. The Church encourages all believers to follow this path. It teaches that small acts of love, done in faith, have eternal value. This perspective transforms daily life into a witness to God’s grace. The Catechism ties this to the call to love God and neighbor. It is a lived theology, not a theoretical one (CCC 2447).

Addressing Common Misunderstandings

One common misunderstanding is that Catholics believe they “earn” salvation through works. This is not the Church’s teaching. Salvation remains a gift, unmerited by human effort. Works are a response to that gift, not a payment for it. Another misconception is that faith is less important in Catholic theology. In reality, faith is foundational—it initiates and sustains the Christian life. The Church simply insists that true faith bears fruit. Some also confuse Catholic teaching with legalism, a focus on rules over relationship. However, the emphasis is on love, not mere duty. Clarity on these points helps bridge gaps with other Christian traditions (CCC 1996-2005).

Critics sometimes point to apparent contradictions in scripture. For instance, Paul’s focus on faith in Romans seems at odds with James’s focus on works. Yet, Catholic theology sees no conflict. Paul addresses the initial gift of justification, which comes through faith. James speaks to its ongoing expression in a believer’s life. The Church teaches that both are true, addressing different aspects of salvation. This synthesis reflects a commitment to the full witness of scripture. It avoids reducing complex truths to simple slogans. The Catechism offers a coherent framework for understanding these texts. It invites believers to see faith and works as partners, not rivals (CCC 1814-1816).

Theological Implications of Faith and Works

The Catholic view of faith and works has deep theological implications. It affirms human dignity by recognizing free will. People are not passive recipients of grace but active participants in God’s plan. This cooperation reflects the relational nature of salvation. God invites humans into a covenant, not a transaction. The doctrine also underscores the importance of community. Works often involve others—serving, teaching, or forgiving—building up the Body of Christ. Faith, while personal, is never solitary in Catholic thought. It finds its fullest expression in love for others. This balance shapes the Church’s mission in the world (CCC 2010-2011).

The teaching also connects to eschatology, or the study of the end times. Catholics believe that faith and works influence one’s eternal destiny. Matthew 25:31-46 ties judgment to how faith was lived out. The Church does not teach that works guarantee salvation apart from grace. Rather, they show whether faith was genuine. This perspective motivates believers to take their actions seriously. It also offers hope, as God’s grace empowers even imperfect efforts. The Catechism frames this as a call to perseverance. It links daily choices to the ultimate goal of union with God. Thus, faith and works together prepare the soul for eternity (CCC 1035).

Ecumenical Perspectives and Modern Dialogue

In recent decades, Catholic teaching on faith and works has been part of ecumenical discussions. The Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification, signed in 1999, marked a milestone. It showed that Catholics and Lutherans share much common ground. Both affirm that salvation comes through grace, received in faith. Differences remain, particularly on the role of works, but the gap has narrowed. The declaration clarified that Catholics do not see works as earning salvation. Lutherans, meanwhile, recognize that faith naturally leads to good deeds. This dialogue reflects a desire for unity among Christians. It also highlights the Catholic commitment to its historic teaching. The Church continues to engage other traditions on this topic (CCC 818-819).

Modern Catholic theologians build on this progress. They emphasize that faith and works are not opposed but complementary. Some Protestant scholars now see value in this view, moving beyond Reformation-era polemics. The Catholic position offers a framework for understanding human responsibility. It avoids both complacency and despair. The Church presents this teaching as a gift to the wider Christian community. It invites reflection on how faith shapes life. Ecumenical efforts show that shared scripture can lead to shared insights. The Catechism remains a key resource in these conversations. It provides a clear, consistent voice for Catholic doctrine (CCC 1987-1995).

Conclusion: A Unified Vision of Salvation

The Catholic doctrine on faith and works offers a unified vision of salvation. It begins with God’s grace, received through faith, and lived out in love. This teaching avoids separating what God has joined together. Scripture, tradition, and the Catechism all affirm this balance. Faith is the root, works are the fruit, and grace is the source. The Church calls believers to embrace both, trusting in God’s mercy. This doctrine is not a burden but a path to holiness. It reflects the fullness of the Christian life. Catholics see it as a response to Christ’s command to love. Ultimately, it points to the heart of the Gospel—relationship with God and neighbor (CCC 2068).

Signup for our Exclusive Newsletter

- Add CatholicShare as a Preferred Source on Google

- Join us on Patreon for premium content

- Checkout these Catholic audiobooks

- Get FREE Rosary Book

- Follow us on Flipboard

-

Discover hidden wisdom in Catholic books; invaluable guides enriching faith and satisfying curiosity. Explore now! #CommissionsEarned

- The Early Church Was the Catholic Church

- The Case for Catholicism - Answers to Classic and Contemporary Protestant Objections

- Meeting the Protestant Challenge: How to Answer 50 Biblical Objections to Catholic Beliefs

As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. Thank you.