Founder of western monasticism, born at Nursia, c. 480; died at Monte Cassino, 543. The only authentic life of Benedict of Nursia is that contained in the second book of St. Gregory’s “Dialogues”. It is rather a character sketch than a biography and consists, for the most part, of a number of miraculous incidents, which, although they illustrate the life of the saint, give little help towards a chronological account of his career. St. Gregory’s authorities for all that he relates were the saint’s own disciples, viz. Constantinus, who succeeded him as Abbot of Monte Cassino; and Honoratus, who was Abbot of Subiaco when St. Gregory wrote his “Dialogues”.

Benedict was the son of a Roman noble of Nursia, a small town near Spoleto, and a tradition, which St. Bede accepts, makes him a twin with his sister Scholastica. His boyhood was spent in Rome, where he lived with his parents and attended the schools until he had reached his higher studies. Then “giving over his books, and forsaking his father’s house and wealth, with a mind only to serve God, he sought for some place where he might attain to the desire of his holy purpose; and in this sort he departed [from Rome], instructed with learned ignorance and furnished with unlearned wisdom” (Dial. St. Greg., II, Introd. in Migne, P.L. LXVI). There is much difference of opinion as to Benedict’s age at the time. It has been very generally stated as fourteen, but a careful examination of St. Gregory’s narrative makes it impossible to suppose him younger than nineteen or twenty. He was old enough to be in the midst of his literary studies, to understand the real meaning and worth of the dissolute and licentious lives of his companions, and to have been deeply affected himself by the love of a woman (Ibid. II, 2). He was capable of weighing all these things in comparison with the life taught in the Gospels, and chose the latter, He was at the beginning of life, and he had at his disposal the means to a career as a Roman noble; clearly he was not a child, As St. Gregory expresses it, “he was in the world and was free to enjoy the advantages which the world offers, but drew back his foot which he had, as it were, already set forth in the world” (ibid., Introd.). If we accept the date 480 for his birth, we may fix the date of his abandoning the schools and quitting home at about A.D. 500.

Benedict does not seem to have left Rome for the purpose of becoming a hermit, but only to find some place away from the life of the great city; moreover, he took his old nurse with him as a servant and they settled down to live in Enfide, near a church dedicated to St. Peter, in some kind of association with “a company of virtuous men” who were in sympathy with his feelings and his views of life. Enfide, which the tradition of Subiaco identifies with the modern Affile, is in the Simbrucini mountains, about forty miles from Rome and two from Subiaco. It stands on the crest of a ridge which rises rapidly from the valley to the higher range of mountains, and seen from the lower ground the village has the appearance of a fortress. As St. Gregory’s account indicates, and as is confirmed by the remains of the old town and by the inscriptions found in the neighbourhood, Enfide was a place of greater importance than is the present town. At Enfide Benedict worked his first miracle by restoring to perfect condition an earthenware wheat-sifter (capisterium) which his old servant had accidentally broken. The notoriety which this miracle brought upon Benedict drove him to escape still farther from social life, and “he fled secretly from his nurse and sought the more retired district of Subiaco”. His purpose of life had also been modified. He had fled Rome to escape the evils of a great city; he now determined to be poor and to live by his own work. “For God’s sake he deliberately chose the hardships of life and the weariness of labour” (ibid., 1).

A short distance from Enfide is the entrance to a narrow, gloomy valley, penetrating the mountains and leading directly to Subiaco. Crossing the Anio and turning to the right, the path rises along the left face oft the ravine and soon reaches the site of Nero’s villa and of the huge mole which formed the lower end of the middle lake; across the valley were ruins of the Roman baths, of which a few great arches and detached masses of wall still stand. Rising from the mole upon twenty five low arches, the foundations of which can even yet be traced, was the bridge from the villa to the baths, under which the waters of the middle lake poured in a wide fall into the lake below. The ruins of these vast buildings and the wide sheet of falling water closed up the entrance of the valley to St. Benedict as he came from Enfide; to-day the narrow valley lies open before us, closed only by the far off mountains. The path continues to ascend, and the side of the ravine, on which it runs, becomes steeper, until we reach a cave above which the mountain now rises almost perpendicularly; while on the right hand it strikes in a rapid descent down to where, in St. Benedict’s day, five hundred feet below, lay the blue waters of the lake. The cave has a large triangular-shaped opening and is about ten feet deep. On his way from Enfide, Benedict met a monk, Romanus, whose monastery was on the mountain above the cliff overhanging the cave. Romanus had discussed with Benedict the purpose which had brought him to Subiaco, and had given him the monk’s habit. By his advice Benedict became a hermit and for three years, unknown to men, lived in this cave above the lake. St. Gregory tells us little of these years, He now speaks of Benedict no longer as a youth (puer), but as a man (vir) of God. Romanus, he twice tells us, served the saint in every way he could. The monk apparently visited him frequently, and on fixed days brought him food.

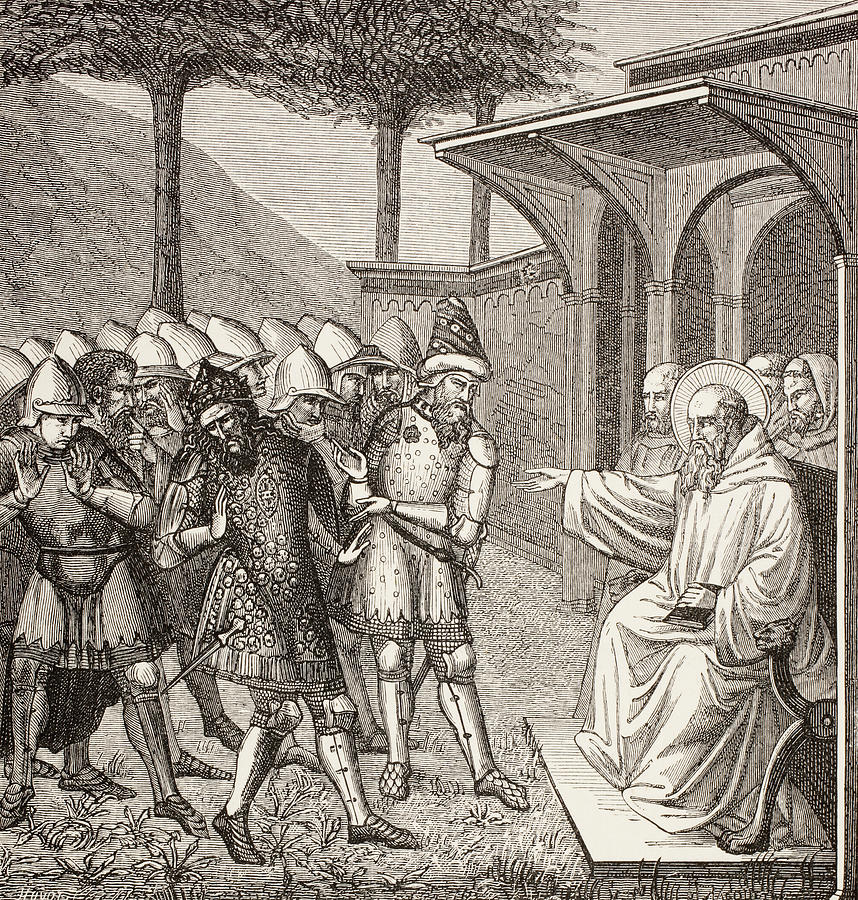

During these three years of solitude, broken only by occasional communications with the outer world and by the visits of Romanus, he matured both in mind and character, in knowledge of himself and of his fellow-man, and at the same time he became not merely known to, but secured the respect of, those about him; so much so that on the death of the abbot of a monastery in the neighbourhood (identified by some with Vicovaro), the community came to him and begged him to become its abbot. Benedict was acquainted with the life and discipline of the monastery, and knew that “their manners were diverse from his and therefore that they would never agree together: yet, at length, overcome with their entreaty, he gave his consent” (ibid., 3). The experiment failed; the monks tried to poison him, and he returned to his cave. From this time his miracles seen to have become frequent, and many people, attracted by his sanctity and character, came to Subiaco to be under his guidance. For them he built in the valley twelve monasteries, in each of which he placed a superior with twelve monks. In a thirteenth he lived with “a few, such as he thought would more profit and be better instructed by his own presence” (ibid., 3). He remained, however, the father or abbot of all. With the establishment of these monasteries began the schools for children; and amongst the first to be brought were Maurus and Placid.

The remainder of St. Benedict’s life was spent in realizing the ideal of monasticism which he has left us drawn out in his Rule.