Brief Overview

- The Fellowship of the Ring, published in 1954 by J.R.R. Tolkien, emerged from a deeply Catholic imagination shaped by the author’s faith and the historical context of early 20th-century England.

- Tolkien, a devout Catholic, lived through World War I and witnessed the rise of industrialization, which influenced his portrayal of good versus evil in Middle-earth.

- The novel’s emphasis on fellowship, sacrifice, and resisting temptation mirrors Catholic teachings prevalent during Tolkien’s lifetime, particularly those found in the Catechism of the Catholic Church (CCC).

- Historically, Tolkien’s work stands apart from secular literary trends of his era, embedding theological depth into a fantasy narrative.

- The One Ring symbolizes the burden of sin, a concept rooted in Catholic doctrine and reflective of medieval Christian allegory.

- The book’s publication came at a time when Catholicism in England was reasserting its intellectual presence, influencing Tolkien’s symbolic framework.

Detailed Response

Historical Context of Tolkien’s Catholic Faith

J.R.R. Tolkien was born in 1892, a time when Catholicism in England was still recovering from centuries of suppression following the Reformation. His mother, Mabel, converted to Catholicism in 1900, a decision that shaped Tolkien’s upbringing and worldview. This conversion came at a personal cost, as it estranged her from family and friends, reinforcing in Tolkien a sense of faith as a sacrificial commitment. Living in an England dominated by Protestantism, Tolkien grew up with an awareness of Catholicism as a minority tradition. His education at Oxford, where he later became a professor, exposed him to medieval literature steeped in Christian themes. World War I, in which he served, further deepened his understanding of suffering and camaraderie, elements that permeate The Fellowship of the Ring. The early 20th century also saw a Catholic literary revival, with figures like G.K. Chesterton influencing intellectual circles Tolkien frequented. This historical backdrop provided fertile ground for his symbolic storytelling. The industrial revolution, which Tolkien viewed with suspicion, also informed his critique of power and corruption. Thus, his faith and historical context are inseparable from the novel’s meaning.

Tolkien’s Intentional Catholic Symbolism

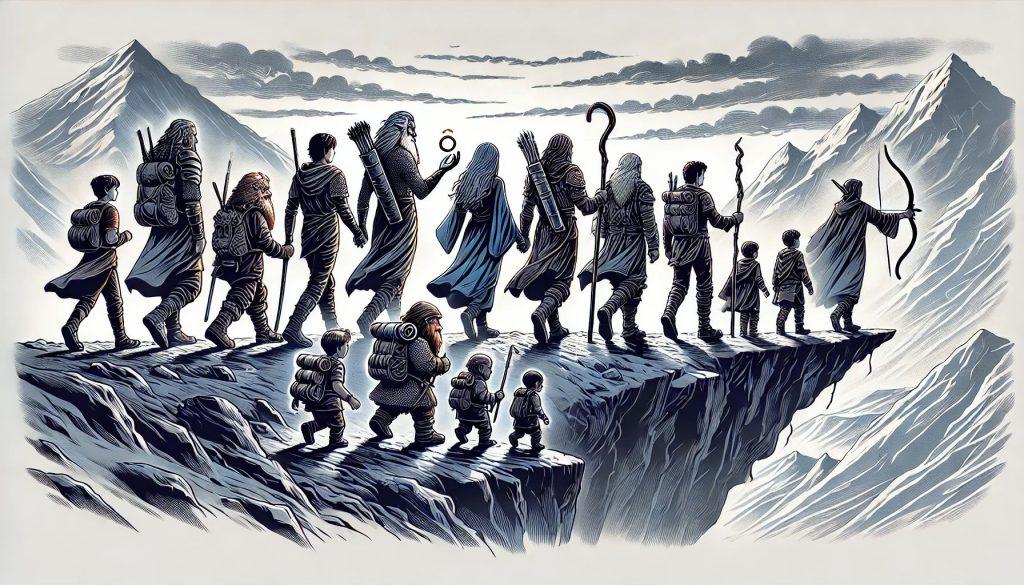

Tolkien famously stated that The Lord of the Rings was “a fundamentally religious and Catholic work,” though he avoided explicit allegory. Unlike C.S. Lewis, whose Narnia series directly reflects Christian narratives, Tolkien preferred subtle, integrated symbolism. He believed that stories should reflect truth naturally, without forcing doctrine onto the reader. This approach aligns with Catholic tradition, which values mystery and the organic presence of faith in human experience. In The Fellowship of the Ring, the group of hobbits, men, an elf, a dwarf, and a wizard represents a unity amidst diversity, echoing the Church as a universal body. Their shared mission to destroy the One Ring suggests a collective struggle against evil, a theme central to Catholic teaching (see CCC 391-395). Tolkien’s letters reveal his intent to craft a mythology that harmonized with Christian truths. His Catholic imagination shaped characters and events to reflect virtues like hope and perseverance. The historical influence of medieval Christian epics, such as Beowulf, also guided his symbolic structure. This intentionality makes the novel a rich field for Catholic interpretation.

The One Ring as a Symbol of Sin

The One Ring stands as the most potent symbol in Tolkien’s narrative, embodying the Catholic understanding of sin’s allure and destructiveness. It tempts all who encounter it, promising power while enslaving its bearer, much like sin’s deceptive pull (see CCC 1849-1851). Frodo Baggins, tasked with carrying the Ring, experiences its weight as a growing burden, paralleling the spiritual struggle against personal fault. The Ring’s ability to corrupt even the virtuous, such as Boromir, reflects the universal human susceptibility to evil. Its creation by Sauron, a figure of pride and rebellion, recalls the fall of Lucifer in Catholic theology (Isaiah 14:12-15). Medieval Christian allegory often used objects to represent moral truths, a tradition Tolkien drew upon. The Ring’s ultimate goal—to dominate all life—mirrors sin’s tendency to isolate and dehumanize. Frodo’s journey to destroy it signifies the arduous path of repentance and redemption. The historical context of Tolkien’s era, marked by totalitarian regimes, may have amplified this symbol’s resonance. Thus, the Ring encapsulates a profound Catholic meditation on human frailty.

Fellowship and the Church

The titular Fellowship represents a community bound by a common purpose, akin to the Catholic Church as the Body of Christ (see CCC 787-796). Frodo, Aragorn, Gandalf, and the others each bring unique strengths, reflecting the diversity of gifts within the Church (1 Corinthians 12:4-11). Their unity is tested by hardship, yet their commitment to the mission endures, illustrating the Church’s call to perseverance. Tolkien’s experience of camaraderie in the trenches of World War I likely informed this portrayal. The Fellowship’s willingness to sacrifice—seen in Gandalf’s fall in Moria—echoes Christ’s self-giving love, a cornerstone of Catholic teaching (see CCC 616). Historically, the early Christian emphasis on communal support influenced Tolkien’s vision. The group’s interdependence counters the Ring’s isolating power, suggesting that salvation is found in relationship, not solitude. This theme resonates with the Church’s role as a communal path to God. Tolkien’s medieval influences, such as the knights of Arthurian legend, further shaped this symbol. The Fellowship thus becomes a living image of Catholic ecclesiology.

Sacrifice and Redemption

Sacrifice permeates The Fellowship of the Ring, reflecting the Catholic theology of redemption through self-offering (see CCC 606-618). Frodo’s acceptance of the Ring’s burden, despite its toll, mirrors Christ’s voluntary suffering for humanity (Philippians 2:6-8). Gandalf’s confrontation with the Balrog, resulting in his apparent death, serves as a sacrificial act to save the Fellowship. Aragorn’s choice to aid Frodo rather than claim the throne early shows a renunciation of personal ambition for a greater good. These acts align with the Catholic call to take up one’s cross (Matthew 16:24). Tolkien’s wartime experiences underscored the nobility of such sacrifices, rooting them in historical reality. The medieval Christian ideal of the martyr also informs this theme. The narrative suggests that redemption comes through enduring suffering, not avoiding it. This message would have struck a chord in post-war England, where loss was familiar. Sacrifice, then, is a pathway to victory over evil in Tolkien’s Catholic framework.

The Role of Hobbits as Humble Servants

Hobbits, particularly Frodo and Sam, embody humility, a virtue exalted in Catholic teaching (see CCC 2554). Small and unassuming, they contrast with the grand figures of Middle-earth, yet they carry the greatest responsibility. This reflects the Gospel paradox that the lowly are chosen for great things (Matthew 5:5). Sam’s loyalty to Frodo mirrors the faithful service of a disciple, rooted in love rather than power. Tolkien’s affection for ordinary English folk, evident in his letters, shaped these characters. Historically, the hobbits recall the medieval peasant, often overlooked yet vital to society. Their resilience against the Ring’s temptation highlights the strength found in simplicity. Catholic tradition honors such figures—saints like Thérèse of Lisieux—who triumph through humility. The hobbits’ role underscores that God’s grace works through the weak (1 Corinthians 1:27). This symbolism elevates their journey into a Catholic parable.

Gandalf as a Christ Figure

Gandalf’s role in the Fellowship carries echoes of Christ, though Tolkien avoided a direct parallel. His wisdom guides the group, much like Christ’s teaching leads the Church (see CCC 551). His sacrifice in Moria, followed by a later return in The Two Towers, suggests a death and resurrection motif (John 11:25). Tolkien’s medieval influences, such as the wise magi of Christian lore, shaped Gandalf’s character. His resistance to wielding the Ring’s power reflects Christ’s rejection of worldly dominion (Matthew 4:8-10). Historically, Tolkien’s era saw a renewed interest in Christocentric theology, influencing this portrayal. Gandalf’s humility—he serves rather than rules—aligns with Catholic ideals of leadership. His presence offers hope, a key Christian virtue (see CCC 1817-1821). While not an allegory, Gandalf’s traits invite Catholic reflection on divine guidance. He stands as a symbol of providence in Middle-earth.

Aragorn and the Kingship of Christ

Aragorn, the heir to Gondor’s throne, symbolizes the restoration of rightful authority, akin to Christ’s kingship (see CCC 668-670). His hidden identity as a ranger parallels Christ’s humble earthly life before His glorification (Philippians 2:7). Aragorn’s reluctance to claim power prematurely reflects a rejection of pride, a Catholic virtue. His leadership in the Fellowship prefigures his eventual reign, much like Christ’s preparation for His eternal rule. Tolkien’s love for medieval kingship narratives, such as Arthur’s legend, informs this character. Historically, the decline of monarchy in Tolkien’s time may have fueled his idealization of just rule. Aragorn’s healing hands, seen later in the trilogy, evoke Christ as healer (Mark 1:34). His journey suggests that true authority serves, aligning with Catholic teaching (Matthew 20:28). This symbolism ties earthly kingship to divine order. Aragorn thus reflects a Catholic vision of leadership.

Nature and Stewardship

Tolkien’s depiction of Middle-earth’s natural beauty reflects the Catholic call to stewardship (see CCC 2415-2418). The hobbits’ love for the Shire contrasts with the destruction wrought by Sauron’s forces, symbolizing the tension between creation and corruption. Tolkien’s disdain for industrialization, evident in his letters, informs this critique. The Ents, guardians of the forest, embody a protective care for the earth, rooted in medieval Christian respect for God’s works. Frodo’s mission preserves Middle-earth’s freedom, suggesting a duty to safeguard creation (Genesis 2:15). Historically, the early 20th-century environmental concerns Tolkien witnessed shaped this theme. Catholic theology views nature as a reflection of God’s goodness, a belief mirrored in the narrative. The Ring’s desolation of the land underscores sin’s harm to creation. This symbolism calls readers to responsible care for the world. It ties Tolkien’s faith to his ecological vision.

Temptation and Moral Struggle

The Ring’s constant temptation tests the Fellowship, reflecting the Catholic understanding of moral struggle (see CCC 1264). Frodo’s internal battle with its influence mirrors the human conflict between grace and sin. Boromir’s fall to its lure shows the danger of pride, a recurring theme in Catholic teaching (James 4:6). Gandalf and Galadriel’s refusal of the Ring highlight the victory of self-mastery. Tolkien’s medieval sources, like Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, often explored such trials. Historically, his era’s moral upheavals—war and greed—amplified this focus. The narrative suggests that resisting evil requires vigilance and support, a Catholic principle. Each character’s response to temptation reveals their moral core. This theme underscores the reality of free will in Catholic doctrine. It frames the Fellowship’s quest as a spiritual battle.

Hope Amidst Darkness

Hope drives the Fellowship forward, a virtue central to Catholic faith (see CCC 1817-1821). Despite overwhelming odds, Frodo persists, sustained by Sam’s fidelity and Gandalf’s guidance. This reflects the Christian belief in light prevailing over darkness (John 1:5). Tolkien’s wartime experience, where hope was scarce, informed this emphasis. The medieval Christian tradition of enduring trial with faith also shapes the narrative. The Ring’s despair-inducing power contrasts with the Fellowship’s resilience, suggesting grace’s triumph. Historically, post-war England needed such a message of perseverance. Catholic theology sees hope as trust in God’s promises, mirrored in the story’s tone. This symbolism offers a counterpoint to secular cynicism. It positions the novel as a testament to enduring faith.

The Role of Providence

Providence subtly guides the Fellowship, aligning with Catholic belief in God’s plan (see CCC 302-314). Gandalf’s selection of Frodo as Ring-bearer hints at a higher purpose, like divine election (Ephesians 1:4). Bilbo’s finding of the Ring, recounted in The Hobbit, is framed as no accident. Tolkien’s letters affirm his belief in a providential order beneath the story. Medieval Christian narratives often attributed events to God’s will, influencing this theme. Historically, Tolkien’s faith offered solace amid 20th-century chaos. The Fellowship’s unlikely success suggests that small acts contribute to a greater design. This idea comforts Frodo when despair looms. Catholic teaching holds that providence works through human freedom, a balance Tolkien maintains. The narrative thus reflects a Catholic trust in divine oversight.

Evil’s Self-Destruction

Sauron’s downfall, foreshadowed in The Fellowship, illustrates the Catholic view that evil destroys itself (see CCC 395). The Ring’s power consumes its wielders, as seen in Gollum’s wretched state. This reflects the biblical truth that sin leads to death (Romans 6:23). Tolkien’s medieval influences, like Dante’s Inferno, depict evil as ultimately futile. Historically, the collapse of tyrannical regimes in Tolkien’s lifetime reinforced this idea. The Fellowship’s role is to resist, not defeat, evil directly, trusting in its inherent weakness. Catholic theology teaches that God’s justice prevails, a belief woven into the story. The Ring’s destruction—achieved later—confirms this pattern. This symbolism critiques power divorced from goodness. It offers a moral lesson rooted in faith.

The Burden of Duty

Frodo’s acceptance of the Ring’s burden symbolizes the Catholic call to duty (see CCC 2238-2240). He does not seek glory but acts out of necessity, reflecting obedience to a higher call (Luke 17:10). Sam’s support exemplifies the duty to aid others, a communal aspect of Catholic life. Tolkien’s wartime sense of obligation likely shaped this theme. Medieval Christian knights, bound by honor, also inform Frodo’s resolve. Historically, duty was a virtue in Tolkien’s England, facing global crises. The narrative suggests that faithfulness to one’s task outweighs personal comfort. Frodo’s struggle humanizes this ideal, showing its cost. Catholic teaching values such fidelity as a path to holiness. This symbolism elevates duty into a sacred act.

Friendship as a Virtue

The bond between Frodo and Sam highlights friendship as a Catholic virtue (see CCC 1939). Their mutual support counters the Ring’s isolating pull, reflecting love as the heart of Christian ethics (John 15:13). Tolkien’s own friendships, like those in the Inklings, inspired this portrayal. Historically, the communal spirit of wartime England echoes in their loyalty. Medieval Christian writings, such as Aelred of Rievaulx’s on spiritual friendship, resonate here. The narrative shows that friendship sustains moral strength, a Catholic insight. Sam’s refusal to abandon Frodo mirrors the Church’s call to solidarity. This theme contrasts with modern individualism. It positions friendship as essential to the good life. Tolkien’s Catholic lens thus sanctifies human connection.

The Universality of the Struggle

The Fellowship’s diverse members—hobbits, men, elf, dwarf—suggest a universal struggle against evil, akin to the Church’s catholicity (see CCC 830-831). Each race brings its perspective, yet all share the mission, reflecting humanity’s common plight (Romans 3:23). Tolkien’s medieval influences, with their broad casts, shaped this inclusivity. Historically, his era’s global conflicts underscored a shared human fate. The Ring threatens all, uniting them in purpose, much like sin’s universal reach. Catholic teaching embraces all peoples in its scope, mirrored in the narrative. The story’s appeal across cultures stems from this breadth. It suggests that goodness transcends boundaries. This symbolism aligns with Tolkien’s faith in a universal truth. It frames Middle-earth as a microcosm of Creation.

Tolkien’s Legacy in Catholic Thought

The Fellowship of the Ring endures as a Catholic touchstone, blending faith with imagination. Tolkien’s subtle approach invites reflection rather than preaching, a method suited to his scholarly temperament. Its symbols—sin, sacrifice, fellowship—resonate with the Catechism’s teachings. Historically, its 1954 publication marked a moment when Catholic voices were gaining literary ground. The novel’s depth rewards study, offering insights into human nature and divine order. Tolkien’s medieval roots ground it in a tradition familiar to Catholic theology. Its popularity suggests a hunger for meaning beyond materialism. Catholic educators and readers continue to find value in its lessons. This legacy reflects Tolkien’s intent to craft a story true to his faith. It remains a testament to the power of Catholic imagination.

Conclusion: A Catholic Lens on Middle-earth

Tolkien’s The Fellowship of the Ring offers a rich field of Catholic symbolism, rooted in his faith and historical context. The One Ring, the Fellowship, and characters like Frodo and Gandalf reflect truths about sin, community, and redemption. These elements align with Catholic doctrine, as seen in references to the Catechism. Tolkien’s medieval influences and 20th-century experiences deepen the narrative’s resonance. The story avoids allegory, instead embedding faith naturally into its fabric. Its themes of sacrifice, hope, and duty speak to universal human concerns. Catholic readers find in it a mirror of their beliefs, expressed through fantasy. Historically, it stands as a counterpoint to secular trends, affirming spiritual realities. Tolkien’s work thus bridges faith and literature with lasting impact. Middle-earth, through a Catholic lens, becomes a place of profound moral clarity.