Brief Overview

- The oldest pictures of Jesus date back to the early centuries of Christianity, offering a glimpse into how early Christians viewed their Savior.

- These images are found in places like catacombs, churches, and ancient manuscripts, reflecting the art and culture of their time.

- Most of these early depictions differ from modern images of Jesus, often showing Him as a youthful, beardless figure or a shepherd.

- Scholars study these artworks to understand the development of Christian iconography and theology.

- The Catholic Church has historically supported sacred art as a tool for teaching and devotion, guided by its traditions.

- This article explores the origins, styles, and significance of these early images from a Catholic perspective.

Detailed Response

The Beginnings of Christian Art

The earliest known pictures of Jesus emerged in a time when Christianity was still a persecuted religion. These images appeared around the 2nd and 3rd centuries, often in hidden places like the Roman catacombs. Christians used art to express their faith discreetly, avoiding attention from Roman authorities. The catacombs, underground burial sites, became a canvas for simple paintings and carvings. Jesus was frequently shown as a young man with short hair, without a beard, which contrasts with later bearded portrayals. This youthful depiction may have been influenced by Roman artistic styles, where gods and heroes were often shown as young and strong. The art was not meant to be a literal portrait but a symbol of hope and salvation. For Catholics, these early works highlight the Church’s long-standing use of images to teach the faith. The Catechism of the Catholic Church (CCC 1159-1162) explains how sacred art points to spiritual truths. Thus, these first images served both a practical and a theological purpose.

The Catacombs of Rome

One key location for the oldest pictures of Jesus is the catacombs of Rome, such as those of Priscilla and Callixtus. These underground tunnels hold paintings dating back to around 200 AD. A common image is Jesus as the Good Shepherd, carrying a lamb on His shoulders. This portrayal draws from John 10:11, where Jesus calls Himself the shepherd who lays down His life for His sheep. The Good Shepherd image was simple yet rich in meaning, reminding early Christians of Christ’s care and sacrifice. The paintings used basic colors like red, green, and yellow, applied to plaster walls. Unlike later detailed icons, these were rough and functional, made under difficult conditions. For Catholics, this art reflects the Church’s roots in a persecuted community that valued symbolic expression. The lack of realistic detail shows that the focus was on Christ’s role, not His physical appearance. These works remain a testament to the faith of the early Church.

The Dura-Europos Church

Another significant find is the house church in Dura-Europos, Syria, dating to around 235 AD. This is one of the oldest known Christian worship spaces, with wall paintings of Jesus. One scene shows Him healing the paralytic, based on Mark 2:1-12. Here, Jesus is again depicted as a young, beardless figure in a Roman tunic. The style mirrors local art traditions, blending Christian themes with regional influences. This suggests early Christians adapted existing artistic forms to share their beliefs. The Dura-Europos images are among the earliest narrative depictions of Jesus’ miracles. For Catholics, these paintings affirm the Church’s emphasis on Christ’s divine power and mercy. They also show how art was used to teach the Gospel in a pre-literate society. The CCC (1160) notes that such images help the faithful contemplate the mysteries of faith.

Why No Portraits?

No contemporary portraits of Jesus exist from His lifetime, which raises questions about these early images. The Gospels do not describe His physical appearance, leaving artists free to interpret His likeness. Early Christians may have avoided realistic portraits to focus on His divine nature rather than His human form. This aligns with Jewish traditions against graven images, which influenced the first believers. Instead, symbolic figures like the Good Shepherd or the healer became common. These choices reflect a theological priority: Jesus as Savior, not as a historical figure to be captured in detail. For Catholics, this absence of portraits underscores the mystery of the Incarnation. The Church teaches that Christ’s true image is spiritual, seen in His actions and presence (CCC 2129-2132). Early art thus served as a tool for meditation, not documentation. This approach shaped Christian iconography for centuries.

The Shift to Bearded Images

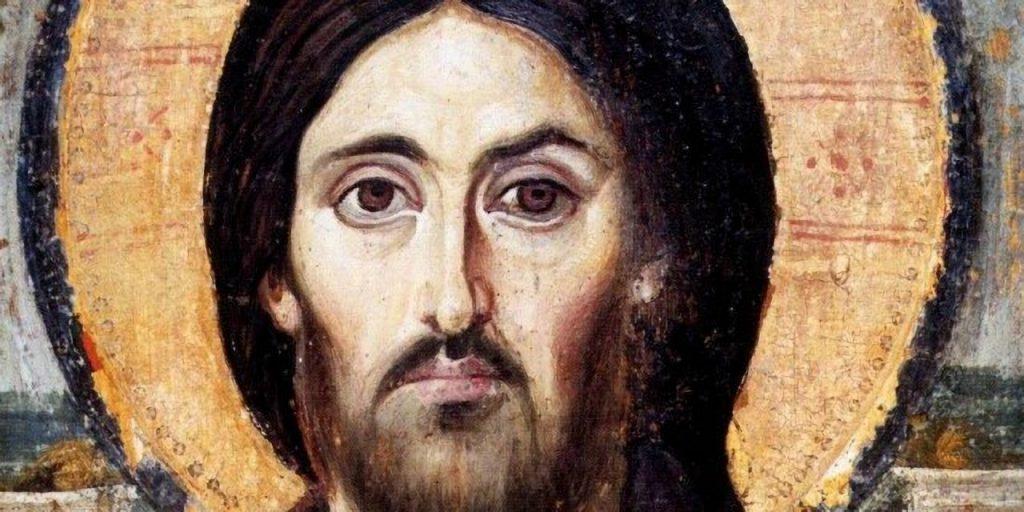

By the 4th century, pictures of Jesus began to change, especially after Christianity became legal in the Roman Empire. The bearded, long-haired image familiar today started to appear, possibly influenced by depictions of Roman gods like Jupiter. This shift coincided with the construction of grand basilicas, where art became more elaborate. A famous example is the mosaic of Jesus in the Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna, from the 6th century. Here, He is shown with a beard, halo, and regal bearing, emphasizing His divine authority. This change reflects a growing focus on Christ as King and Judge, alongside His role as Shepherd. For Catholics, this evolution shows how the Church adapted its art to new contexts while keeping its core message. The CCC (1161) highlights how such images lift the mind to heavenly realities. The bearded Christ became a standard in Byzantine and medieval art. Yet, the earlier images remind us of the diversity in early Christian expression.

The Role of Sacred Art in Catholicism

The Catholic Church has always seen art as a way to communicate truth, a view rooted in its history. Early pictures of Jesus were not just decoration but tools for catechesis and worship. In a time when few could read, images taught the stories of Scripture. The Second Council of Nicaea in 787 AD affirmed the use of icons, rejecting iconoclasm. This decision clarified that honoring images was not idolatry but a way to honor the reality they represent. For Catholics, this applies to the oldest pictures of Jesus, which point to His saving work. The CCC (1159) explains that sacred art makes the invisible visible in a limited way. These early images, though simple, carried deep meaning for believers. They also built a foundation for the rich tradition of Catholic art. Today, they remain valuable for both history and faith.

Theological Meaning of Early Images

The oldest pictures of Jesus carry theological weight beyond their artistic style. The Good Shepherd, for instance, emphasizes Christ’s role as protector and redeemer. This image connects to Psalm 23 and John 10, linking Old and New Testaments. Early Christians saw Jesus as fulfilling ancient promises, a theme central to Catholic teaching. Other depictions, like the healer or the teacher, highlight His miracles and wisdom. These choices show how art reflected the Church’s understanding of Christ’s identity. For Catholics, such images are not mere history but invitations to reflect on divine truths. The CCC (1162) notes that art can lead believers to contemplate God’s plan of salvation. The simplicity of early images mirrors the humility of Christ’s life. They invite a focus on His mission rather than His appearance.

Preservation and Study

Many of these early pictures have survived due to their locations, like the catacombs or desert churches. Archaeologists and historians work to preserve them, uncovering details about ancient Christian life. The materials—plaster, pigment, stone—were basic but durable, lasting centuries. Modern technology, like infrared imaging, reveals faded details in these works. For Catholics, preserving this art is a way to honor the faith of early believers. The Church has often supported such efforts, seeing value in its heritage. Scholars debate the exact dates and meanings of some images, but their significance is clear. They offer a window into how the first Christians expressed their hope. The CCC (1160) suggests that these works still speak to the faithful today. Their study bridges past and present in the Church’s tradition.

Influence on Later Art

The oldest pictures of Jesus set patterns that influenced Christian art for centuries. The Good Shepherd evolved into more detailed pastoral scenes in medieval works. The beardless youth gave way to the majestic Christ of Byzantine icons. These early forms laid groundwork for the styles of the Middle Ages and Renaissance. For Catholics, this continuity shows the Church’s consistent use of art to proclaim Christ. The CCC (1161) affirms that sacred images remain a vital part of worship. Artists built on these foundations, adapting them to new cultures and times. The simplicity of early images contrasts with later complexity, yet the purpose stayed the same. They all aim to draw people closer to God. This progression highlights the Church’s living tradition.

Catholic Perspective on Images Today

Today, the Catholic Church continues to value sacred art, including the oldest pictures of Jesus. These images are seen as part of a heritage that teaches and inspires. The Church does not claim they show Jesus’ true face but values them as symbols of faith. The CCC (2132) explains that veneration of images is directed to the person they represent, not the object itself. This principle applies to ancient catacomb paintings as much as modern statues. For Catholics, these early works connect them to the first followers of Christ. They remind believers of the Church’s roots in persecution and triumph. The art’s simplicity can still move people to prayer and reflection. It also counters modern skepticism about the Church’s history. These images stand as quiet witnesses to an enduring faith.

Challenges in Interpretation

Interpreting the oldest pictures of Jesus poses challenges for scholars and believers. Their age and condition make some details unclear, leading to debate. Were they purely symbolic, or did they reflect local traditions? The lack of written records from the artists adds to the mystery. For Catholics, this ambiguity is not a problem but part of the art’s depth. The Church teaches that sacred images are aids to faith, not historical documents (CCC 1160). Their meaning lies in what they convey about Christ, not in precise origins. Scholars may differ on dates or styles, but the spiritual value remains. These works invite contemplation rather than definitive answers. They show how faith can thrive in uncertainty.

Cultural Context of Early Images

The oldest pictures of Jesus reflect the cultures where they were made. In Rome, they borrowed from Greco-Roman art, with its clean lines and youthful figures. In Syria, they mixed with Eastern styles, showing local clothing and settings. This blending reveals how Christianity spread across diverse regions. For Catholics, it underscores the Church’s universal nature, adapting yet staying true to its message. The CCC (1202) notes that the Gospel can take root in any culture. Early artists used familiar forms to make Christ accessible to their people. This flexibility helped the faith grow in a divided world. The images thus carry both local and timeless meaning. They bridge human experience and divine truth.

The Good Shepherd’s Lasting Impact

The Good Shepherd remains one of the most enduring early images of Jesus. Its simplicity made it a powerful symbol for persecuted Christians. It spoke of care, safety, and sacrifice in a hostile world. The image appears not just in catacombs but on sarcophagi and lamps, showing its wide use. For Catholics, it captures the heart of Christ’s mission as taught in John 10:14-15. The CCC (1159) sees such symbols as ways to encounter God’s love. Later art expanded on this theme, adding details like flocks or landscapes. Yet the core idea stayed the same: Jesus as the one who seeks and saves. This continuity links early believers to today’s Church. The Good Shepherd still resonates as a sign of hope.

Miracles in Early Art

Depictions of Jesus’ miracles, like the healing at Dura-Europos, highlight His divine power. These scenes were chosen to affirm His identity as God’s Son. They also taught key Gospel events to the illiterate, a practical role in early Christianity. The paralytic’s healing, from Mark 2, showed forgiveness and physical restoration. For Catholics, such images reflect the Church’s belief in Christ’s dual nature, human and divine (CCC 464). The art’s focus on miracles reinforced this truth for early believers. It also offered comfort, showing Jesus’ active presence in suffering. These works were both teaching tools and sources of strength. Their survival preserves this message for modern study. They remind Catholics of Christ’s ongoing work in the world.

Theological Consistency

The oldest pictures of Jesus align with Catholic theology, even in their variety. Whether as Shepherd, healer, or teacher, they emphasize His roles as Savior and Lord. This consistency reflects the Church’s early clarity about Christ’s identity. The art avoided frivolous details, keeping the focus on spiritual meaning. For Catholics, this shows how faith shaped even the simplest expressions. The CCC (1162) notes that sacred art must serve the Church’s mission. These images did so by pointing to Christ’s life and work. They also fit the broader tradition of Scripture and worship. Their theological depth makes them more than historical artifacts. They remain relevant to Catholic belief today.

Art as a Witness to Faith

The oldest pictures of Jesus testify to the courage of early Christians. Created in secret or under threat, they show a faith that endured hardship. Their makers risked much to honor Christ in this way. For Catholics, this witness strengthens the Church’s claim to continuity from apostolic times. The CCC (1160) sees such art as part of the Church’s living memory. These images link believers across centuries, from catacombs to cathedrals. They also challenge modern views that dismiss religious art as superstition. Their survival proves the depth of early devotion. For the Church, they are a call to remember and live that same faith. They stand as quiet but firm evidence of Christ’s impact.

Modern Relevance

Today, the oldest pictures of Jesus still matter to Catholics and scholars alike. They offer a tangible connection to the Church’s beginnings, grounding its traditions. Their simplicity contrasts with modern complexity, inviting reflection. For Catholics, they reinforce the value of sacred art in worship and teaching. The CCC (1159-1162) upholds this role, unchanged since ancient times. These images also counter claims that Christianity lacks historical roots. They show a faith expressed through creativity, even in danger. Modern believers can draw inspiration from their quiet strength. They remind the Church of its mission to proclaim Christ in every age. In a fast-moving world, they call for pause and prayer.

Conclusion: A Legacy of Faith

The oldest pictures of Jesus are more than ancient art; they are a legacy of faith. They reveal how early Christians saw their Lord and shared His story. From catacombs to churches, these images carried the Gospel forward. For Catholics, they affirm the Church’s use of art to lift hearts to God. The CCC (1161) captures this purpose, tying past to present. Their styles may differ—youthful or bearded, simple or grand—but their message unites them. They point to Christ as Shepherd, healer, and King. Studying them deepens understanding of both history and theology. They invite all to see Jesus through the eyes of the first believers. This enduring witness continues to shape Catholic life and devotion.