Brief Overview

- Jesus, as both fully human and fully divine, experienced emotions like sorrow and compassion, which are reflected in moments where he cried.

- The Bible records three specific instances where Jesus shed tears, each tied to significant events in his life and ministry.

- These moments reveal his deep connection to humanity and his participation in human suffering.

- The first instance occurs at the death of Lazarus, showing his empathy and love for his friend.

- The second is when Jesus weeps over Jerusalem, expressing grief for its spiritual state.

- The third happens during his Passion, highlighting his anguish before the crucifixion.

Detailed Response

The Tears at Lazarus’ Tomb

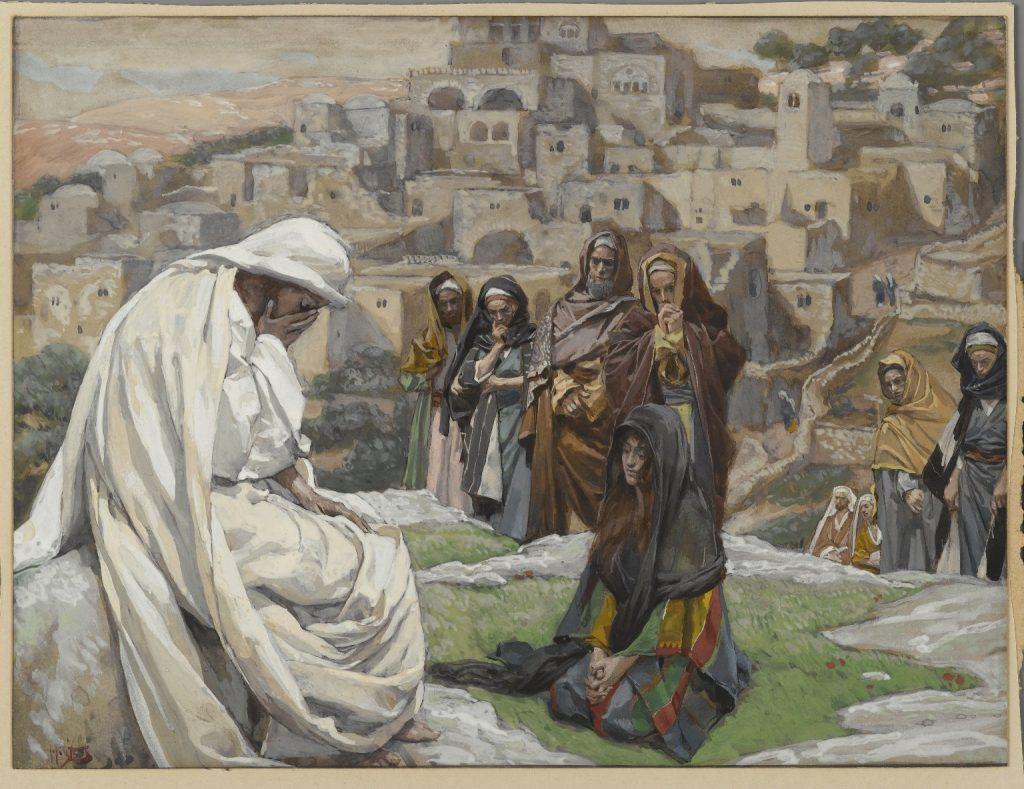

The first recorded instance of Jesus crying is found in John 11, when he learns of the death of Lazarus. This event takes place in Bethany, where Lazarus lived with his sisters, Mary and Martha. When Jesus arrives, he finds that Lazarus has been dead for four days. The text notes that Jesus was “deeply moved in spirit and troubled” upon seeing the grief of those around him. This reaction shows his genuine human emotion, despite his divine power to raise Lazarus. The shortest verse in the Bible, “Jesus wept” (John 11:35), captures this moment succinctly. His tears were not from a lack of faith or power but from compassion for his friends’ pain. This event also foreshadows his own victory over death through the resurrection. The Catechism of the Catholic Church emphasizes Christ’s full humanity in such moments (see CCC 470). Thus, Jesus’ tears here affirm his solidarity with human suffering.

Scholars note that this episode also serves a theological purpose. Jesus delays his arrival intentionally, allowing Lazarus to die, which sets the stage for a miracle. The raising of Lazarus demonstrates his authority over death, a sign pointing to his own resurrection. Yet, his tears remain a powerful sign of his emotional bond with humanity. He does not stand aloof but enters into the sorrow of those he loves. This balance of divine power and human empathy is central to Catholic teaching on the Incarnation. The Church teaches that Jesus took on human nature fully, including its capacity for sorrow (see CCC 472). His weeping was not a performance but a natural response to loss. It also invites believers to trust in his compassion during their own grief. This moment remains a profound example of God’s nearness to human pain.

The Weeping Over Jerusalem

The second instance of Jesus crying occurs in Luke 19:41-44, when he weeps over Jerusalem. As he approaches the city during his triumphal entry, Jesus foresees its future destruction. This event happens shortly before his Passion, adding weight to his emotional response. He laments that Jerusalem did not recognize “the time of your visitation,” meaning its failure to accept him as the Messiah. His tears reflect sorrow for the city’s spiritual blindness and the suffering that will follow. This moment reveals his deep love for his people, even as they reject him. The Catechism highlights Christ’s mission to call all to salvation, which this episode underscores (see CCC 558). His grief is not just personal but prophetic, tied to the fate of God’s chosen people. Historically, Jerusalem was destroyed by the Romans in AD 70, fulfilling his words. Thus, his tears blend human emotion with divine foresight.

This weeping also carries a pastoral lesson for Catholics. Jesus’ sorrow shows his desire for humanity’s repentance and peace. He does not rejoice in judgment but mourns the consequences of sin. Scholars point out that this event echoes Old Testament prophets like Jeremiah, who also wept for Israel’s fate. Jesus, as the fulfillment of the prophets, takes on this role with even greater intensity. His tears challenge believers to consider their own response to God’s call. The Church teaches that Christ continues to intercede for humanity’s salvation (see CCC 2741). This moment also contrasts with the crowd’s joy during the entry, highlighting Jesus’ awareness of what lies ahead. It is a sobering reminder of the cost of rejecting grace. For Catholics, it calls for reflection on personal and communal fidelity to God.

The Agony in the Garden

The third instance of Jesus crying is during his agony in the Garden of Gethsemane, recorded in Luke 22:39-46 and Matthew 26:36-46. While the text does not explicitly say “Jesus wept,” it describes his intense distress, with sweat like “drops of blood.” Catholic tradition and scholars widely interpret this as a moment of tears, given the depth of his anguish. Facing his imminent crucifixion, Jesus prays, “Father, if you are willing, remove this cup from me.” This plea reveals his human dread of suffering and death. Yet, he submits to the Father’s will, saying, “Not my will, but yours be done.” The Catechism explains this as the ultimate act of obedience and love (see CCC 532). His emotional struggle shows that even the Son of God felt the weight of human fear. This moment bridges his divine mission and human vulnerability. It is a cornerstone of Catholic devotion, especially in the Sorrowful Mysteries of the Rosary.

The agony in the garden also teaches about the reality of suffering in the Christian life. Jesus does not avoid pain but faces it with prayer and trust. His tears, whether literal or symbolic, invite believers to unite their struggles with his. The Church sees this as a model for accepting God’s will amid hardship (see CCC 612). Scholars note that the “sweat like blood” may reflect a rare medical condition called hematidrosis, caused by extreme stress. This detail reinforces the intensity of his experience. His disciples, sleeping nearby, fail to support him, adding to his isolation. This scene contrasts with his earlier miracles, showing his willingness to embrace weakness. For Catholics, it affirms that God understands human anguish firsthand. It also prepares the faithful for the redemptive power of the cross that follows.

Theological Significance of Jesus’ Tears

These three instances of Jesus crying carry deep meaning in Catholic theology. They affirm the doctrine of the Incarnation, that Jesus is both fully God and fully man. His tears are not a sign of weakness but a revelation of his shared humanity. The Catechism teaches that Christ assumed all aspects of human nature except sin (see CCC 467). His emotional responses show that feelings like sorrow are not opposed to holiness. Instead, they are sanctified through his experience. Each episode also points to a different facet of his mission: compassion, salvation, and redemption. Together, they paint a picture of a Savior who is not distant but intimately involved in human life. This truth comforts believers facing their own trials. It also deepens the Church’s understanding of God’s love.

The tears of Jesus also connect to Catholic sacramental life. In baptism, believers are united to Christ’s life, including his sorrows (see CCC 1225). His weeping reminds the faithful that God enters into their pain, not just their joy. The Eucharist, as a memorial of his Passion, echoes the agony in the garden. Confession offers healing for the spiritual blindness Jesus mourned in Jerusalem. The raising of Lazarus prefigures the resurrection promised in the last rites. Thus, his tears resonate through the Church’s practices. They also inspire acts of charity, as Catholics are called to share in others’ burdens. Scholars see this as a call to imitate Christ’s empathy. For the Church, these moments are not just historical but living truths.

Practical Lessons for Catholics Today

The tears of Jesus offer practical guidance for Catholic living. His compassion at Lazarus’ tomb encourages believers to support those who grieve. This might mean visiting the sick or comforting the bereaved. His weeping over Jerusalem calls for prayer and action to address spiritual and social ills. Catholics are urged to work for peace and justice in their communities. The agony in the garden teaches perseverance in prayer, even when answers seem far off. It also reminds the faithful to trust God’s plan amid suffering. The Catechism ties this to the virtue of hope (see CCC 1820). These lessons are not abstract but meant to shape daily life. They show that faith involves both heart and action.

Finally, Jesus’ tears challenge modern tendencies to avoid pain or emotion. In a world that often values stoicism or distraction, his example validates honest feeling. Catholics are called to face suffering with faith, not denial. His tears also counter any view of God as cold or detached. Instead, they reveal a Lord who weeps with his people. This truth can strengthen those facing personal loss or global crises. The Church teaches that such solidarity is the heart of the Gospel (see CCC 1503). By reflecting on these moments, believers grow closer to Christ. His tears are a gift, showing that no pain is beyond his reach. They remain a source of hope and renewal for the faithful.